In light of recent events, this week’s issue of The Hard Work of Hope will be a little different. We are always trying to offer poems that meet the moment, and the current crisis in Haiti—along with its long history of instability and the United States’ involvement in it—demands a special response. This week, we bring you a folio of six poems that speak to the Haitian experience, curated and introduced by Danielle Legros Georges:

In the poem “Hard Work,” Kathleen Aguero has us consider the pathways by which hope travels “before it gets to that bubbling place,” that site where it springs eternal. Hope, she writes “forces itself through miles of dirt packed hard/then around, over, under rocks.” An act of determination, hope wills itself “not to dry up in the desert.”

Surely such sturdy hope guided the Haitian migrants who recently made their way to Acuña, Mexico and the Texas border town of Del Rio. Many arrived after perilous months-long journeys across South America, some beginning as far as Chile. A news image of a line of people wading across the Rio Grande River evokes the Biblical, while photographs of the aggression that met them, meted by U.S. federal agents on horseback, telegraph the inhumane.

“No one leaves home” notes poet Warsan Shire, “unless/home is the mouth of a shark.” In the poem “Home,” Shire enumerates the reasons that make refugees:

no one leaves home unless home chases you

fire under feet

hot blood in your belly

it’s not something you ever thought of doing

until the blade burnt threats into

your neck

Such metaphors as exist in her poem apply to much of the history of U.S. immigrants, from the experience of the Puritans to that of the Afghans. The Haitians who gathered at the border articulated the unsustainability of life for them in a country reeling from poverty, natural disasters, security concerns, human rights abuses, and long-standing political instability (underscored most recently by the assassination of the Haitian president in July). Some fled as a result of the gang violence that has pervaded Port-au-Prince. Many left Haiti after the devastating 2010 earthquake and cannot imagine being repatriated to a country whose conditions are exponentially worse than the ones that caused their departures.

Scholars and observers of Haiti correctly point to legacies of Western imperialism and colonialism accompanied by home-grown corruption as lenses through which the root causes of Haitian exoduses can be viewed. Interventions by the United States in Haiti—from a 1915 invasion and occupation, to the propping up of Haiti’s most recent leaders—have played a significant role in Haiti’s precariousness.

The situation at the Texas border revealed a humanitarian crisis, one that threatens the health, safety, and lives of a group of people. The Haitians at the border should be seen as freedom seekers, whose basic stories are not unlike those of most U.S. families, whether arriving here in 1620,1845, or 1990. These Haitians deserve asylum hearings—and the hope that comes with the possibility of better lives here.

I am glad for the voices of Jean-Dany Joachim, Jean-Claude Martineau, Lenelle Moïse, Patrick Sylvain, and Tontongi, writers with Massachusetts connections, Haitian roots, and histories of socially-engaged work. Their poems appear below, along with one of mine. These poets contribute to my education in the Haitian experience; in Haitian courage, resistance, and hope.

Each of the poems is followed by a link to a further reading.

To support Haitian asylum seekers, contact your Congressmember(s) at 202.224.3121. To support relief efforts, visit Diaspora Rising Earthquake Relief Efforts by Haitian and Diaspora led Organizations

POETRY FOLIO

quaking conversation

Lenelle Moïse

i want to talk about haiti.

how the earth had to break

the island’s spine to wake

the world up to her screaming.

how this post-earthquake crisis

is not natural

or supernatural.

i want to talk about disasters.

how men make them

with embargoes, exploitation,

stigma, sabotage, scalding

debt and cold shoulders.

talk centuries

of political corruption

so commonplace

it’s lukewarm, tap.

talk january 1, 1804

and how it shed life.

talk 1937

and how it bled death.

talk 1964. 1986. 1991. 2004. 2008.

how history is the word

that makes today

uneven, possible.

talk new orleans,

palestine, sri lanka,

the bronx and other points

or connection.

talk resilience and miracles.

how haitian elders sing in time

to their grumbling bellies

and stubborn hearts.

how after weeks under the rubble,

a baby is pulled out,

awake, dehydrated, adorable, telling

stories with old-soul eyes.

how many more are still

buried, breathing, praying and waiting?

intact despite the veil of fear and dust

coating their bruised faces?

i want to talk about our irreversible dead.

the artists, the activists, the spiritual leaders,

the family members, the friends, the merchants

the outcasts, the cons.

all of them, my newest ancestors,

all of them, hovering now,

watching our collective response,

keeping score, making bets.

i want to talk about money.

how one man’s recession might be

another man’s unachievable reality.

how unfair that is.

how i see a haitian woman’s face

every time i look down at a hot meal,

slip into my bed, take a sip of water,

show mercy to a mirror.

how if my parents had made different

decisions three decades ago,

it could have been my arm

sticking out of a mass grave

i want to talk about gratitude.

i want to talk about compassion.

i want to talk about respect.

how even the desperate deserve it.

how haitians sometimes greet each other

with the two words “honor”

and “respect.”

how we all should follow suit.

try every time you hear the word “victim,”

you think “honor.”

try every time you hear the tag “john doe,”

you shout “respect!”

because my people have names.

because my people have nerve.

because my people are

your people in disguise

i want to talk about haiti.

i always talk about haiti.

my mouth quaking with her love,

complexity, honor and respect.

come sit, come stand, come

cry with me. talk.

there’s much to say.

walk. much more to do.

Copyright © 2014 by Lenelle Moïse, from her poetry collection Haiti Glass (City Lights Books).

This Evening, I Will Not Cry for My Dead

Jean-Dany Joachim

This evening, I will not cry for my dead

I’ll instead launch their names into the sky

I’ll tear off the stars one by one

And paste in their place the wide-open eyes of the departed.

Let their gaze strike this earth

Gorged with bodies and sweat

And all it hides in its entrails

Let these gazes become lightning, new suns and new moons.

My dead will not see me cry this evening

I’ll sing instead chants of Ibo, Yanvalou, Petwo

Let the tomtoms wake up for the resurrection

Of these souls ripped from life so soon

I’ll not write a single word of death

I call instead for an earthquake of life

To shake the souls in pain

I call on the budding of hope

I give my tears in exchange for life

I will not cry at all for my dead…

Copyright © 2010 by Jean-Dany Joachim, from Poets for Haiti: An Anthology of Poetry and Art; editor, Kim Triedman.

READ “Earthquake Relief Efforts by Haitian and Diaspora led Organizations” by DiasporaRising

Poem for the Poorest Country in the Western Hemisphere

Danielle Legros Georges

O poorest country, this is not your name.

You should be called beacon. You should

be called flame. Almond and bougainvillea,

garden and green mountain, villa and hut,

girl with red ribbons in her hair,

books under arm, charmed by the light

of morning, charcoal seller in black skirt,

encircled by dead trees. You, country,

are merchant woman and eager clerk,

grandfather at the gate, at the crossroads

with the flashlight, with all in sight.

Copyright © 2010 by Danielle Legros Georges, from The Dear Remote Nearness of You (Barrow Street, 2016).

READ “Why Representations of Haiti Matter Now More Than Ever” by Gina Ulysse

Rope Jumping

Patrick Sylvain

I sat on a boulder

By a beach near Saint-Marc,

The small province to the north of Port-au-Prince,

Watching two boys, about 14,

Underneath a flame tree

Fiercely swinging a thick dark brown rope

On a soft creamish dirt road.

Five girls lined up to take turns,

They jumped fearlessly, holding

The bottoms of their skirts.

“Yon dous, yon cho,” one soft, one peppery.

They played under a large flamboyant tree

Avoiding the burning rays of the tropical sun.

Their voices and laughter rose

Resonated like a flock of migrating birds.

Their cadence and agile feet

Transported me to my youth

And the burning joy I felt

When jumping with the girls.

Glistening thighs, firm feet, quick eyes

And the slight touches of the opposite bodies

When playing doubles carried us to a zone

Our parents had traveled and feared.

We were innocent and dangerous.

Our gender differences became the dividing line.

We later took pleasure at watching the girls’ legs

And their solid thighs underneath their flying skirts.

Occasionally, they let us turn the ropes.

And those of us with racing hormones

Became the bad boys’ placards.

“Yon dous, yon cho,” one soft, one peppery.

I wonder what those boys were thinking

As they swung the ropes

For those athletic-bodied girls!

Copyright © 2005 by Patrick Sylvain, from Love, Lust, and Loss (Mémoire D’encrier, 2005).

READ “To Rebuild Haiti After This Earthquake, We Must Empower Haitians,” by Pierre Noel and Karen Ansara

Pseudo-Haiku for Immigrant Haters

Tontongi

You say Go Home! I say Go Home Too!

We all come from a nether space of despair.

I say Let’s All Together Come Home!

Copyright © 2013 by Tontongi, from In the Beast’s Alley (Trilingual Press, 2013).

READ “The Delusion of Borders: On Migrants, Abundance, and Manufactured Scarcity” by Roxane Gay

Vjewo

Jean-Claude Martineau

In the middle of a cane field near Higuey

In the Dominican Republic

Two Haitians sit in a batey

Bare feet, bare backed

One speaks, one heeds

So softly

Only the wind through the cane hears

What they say

Vyewo, you going home to farm in Haiti

Take this parcel to my wife for me

A pair of earrings and ten

Pesos, Vyewo

When you get there, if you find her

Settled down with someone else

Give them to my mother for me

Vyewo set off, Vyewo returned

With news that burned the heart

The mother had died

Some years before

A broken heart

They say

The wife was still there, still hanging on

The kids needed more, the first one grew wild,

The small one didn’t know his father at all.

In the middle of a cane field near Higuey

In the Dominican Republic

Two Haitians sit in a batey

Bare feet, bare backed

One speaks, one heeds

So softly

The wind through the cane hurries

To erase what they say

Cousin, I’ve come from working the earth in Haiti

Here’s the message your wife sends you

It’s time for you to return, Cousin

Even if your hands are empty, Cousin

And remember, Cousin, when you cross the border

Don’t leave your machete behind.

“Vyewo” Copyright © 1991 by Jean-Claude Martineau, from Pwezi, Kont, Chante (Edition Libète).

Translated from the Haitian Creole by Danielle Legros Georges

Lenelle Moïse is the author of Haiti Glass (City Lights Books, 2014). She is a poet, playwright, song-maker and screenwriter. Please visit http://www.lenellemoise.com for more information.

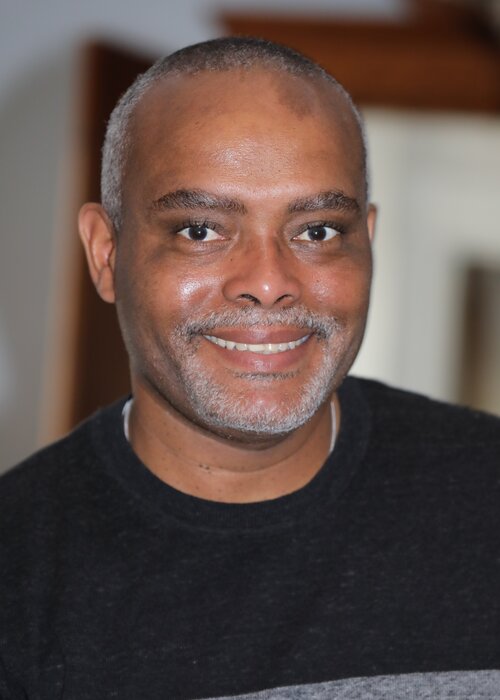

Jean Dany Joachim is a poet, fiction-writer, and playwright. He has four published collections of poetry and a play, Chen Plenn (2007), Crossroads / Chimenkwaze (2013), Avec des Mots (2014), Quartier (2016), and Your Voice Poet / Ta Voix Poète (2017). He created the Many Voices Project, inspiring conversations about race and equality, and he’s director of City Night Readings, a series featuring diverse poetic talents. He is an adjunct professor at Bunker Hill Community College, and he serves on the Board of the New England Poetry Club.

Born in Gonaïves, Haiti, Danielle Legros Georges is the author of several poetry collections including The Dear Remote Nearness of You (Barrow Street, 2016) and Island Heart, translations of the poems of the Haitian-French writer Ida Faubert (Subpress Collective, 2021). Legros Georges directs Lesley University’s MFA Program in Creative Writing. She served as poet laureate of Boston from 2015 through 2019.

Patrick Sylvain is a Haitian-American poet, writer, photographer, social and literary critic who has published widely on Haitian, Haitian diaspora culture, politics, language, and religion. He is the author of several poetry books in English and Haitian, and his poems have been nominated for the prestigious Pushcart Prize. He is published in several anthologies, academic journals, books, magazines and reviews including: African American Review, Agni, American Poetry Review, Callaloo, Chicago Quarterly Review, Ploughshares, Prairie Schooner, Transition, and The Caribbean Writer.

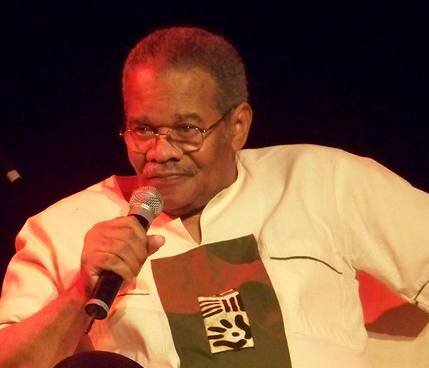

Eddy Toussaint Tontongi was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, and lives now in Watertown, MA. Poet, literary critic, and essayist, he writes in Haitian, French and English. Tontongi’s latest books include Tyaka Poetica, a bilingual collection of essays, memoirs and poems (Trilingual Press, Cambridge, MA, 2021); La Parole indomptée / Memwa Baboukèt (“The Untamed Speech / Memory of The Muzzle,”), published by L’Harmattan, Paris, France, 2015; In the Beast’s Alley, a collection of his “poems of conscience”, (T.P., 2013). The author is working currently on a collection of chronicles and memoirs of life in the United States. Tontongi is the Editor-in-Chief of the publishing house Trilingual Press and the trilingual politico-literary journal Tanbou

(www.tanbou.com).

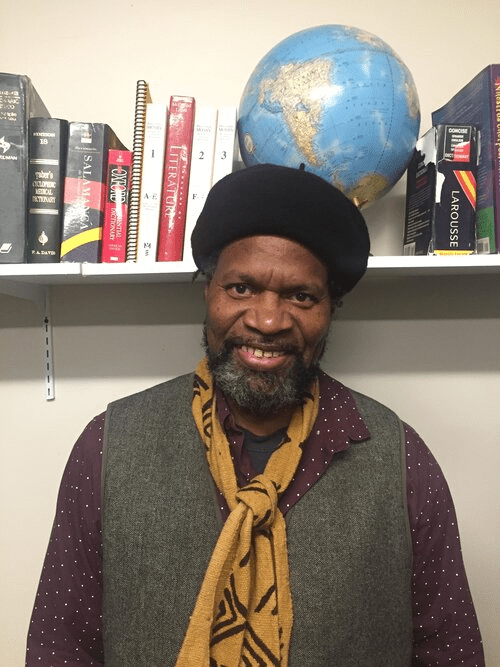

Jean-Claude Martineau is a poet, musician, writer, and activist.