Available now from Presa Press

When did you first encounter poetry? How did you discover you wanted to write poems?

The songs of Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Dion and the Belmonts were the first poems I paid attention to, though none of them would admit they were writing poems. To my teen-age self, their words spoke deeply and personally to me. Then came Bob Dylan and John Lennon lyrics, that actually were often poems. About the same time, my high school senior year English teacher was covering the English Cavalier Poets, whose sense of manhood and honor appealed to me. And I wrote some simple quatrains to impress a few girls in class. It worked. I got phone numbers and dates. Ah, the power of poetry!

Do you have a writing routine? A favorite time or place to write?

I write whenever and however. My first full-length book is titled The Night Watches (1981) because most of the poems in it were written after midnight. I tend write at night, sometimes very late. Usually I also have a blank journal within easy reach to jot down ideas, impressions, phrases, factual details, or whatever that might later becomes poems. This worked exceedingly well on several European vacation trips. I remember standing in the ruins of Delphi, Greece and being so moved by the surroundings and the history that I wrote a poem in my journal right there.

Where do your poems most often come from—an image, a sound, a phrase, an idea?

Often a phrase will come to me and I’ll play with it in my head for weeks, adding lines and images until I finally write it out in on paper to see if it is a poem-in-the-making. Sometimes it is. I remember one time in a restaurant on Cape Cod in June with some friends when, in the middle of dinner and the conversation, I paused, grew silent, and wrote out on the paper napkin, “Believing in Eyes.” That became the title of one poem in the new book that I had been carrying inside of me since Thanksgiving but that I hadn’t yet written down because I had no title for it. Something in our talking must have triggered the title. So the poem was then done and that night in the hotel room I wrote it out on paper. This has become something of a running joke between these friends and my wife and me: “Oh, look, Gary’s working in his head again!”

Another poem in the new book, “Backyard Labyrinth,” is about me mowing the tall grass in the field behind my house where I usually cut a labyrinth in the grass and maintain it as such all summer. It typically takes about a week to mow it down. Of course, larger and better riding lawn mowers than what I have could do it in a day. But one year as I was mowing down a design modeled after the Cretan Maze where the Minotaur hid, I began to compose in my head as I was riding the mower a sort of mock epic about the process.

At a poetry reading by Jack Gilbert at Smith College, one line in a poem he was reciting so moved me that a strong visual memory of my wife kissing her father in the coffin at his wake that I began to write it out in the margins of the reading’s program, and continued on into a sudden and striking and terrible future memory, if such a thing is possible, of me in my own coffin. This poem, “To Purgatory,” is also in the new book. So it’s safe to say that my poems come to me from some immediate inspiration. But the real work is in the process of making the poem from that moment, which can take months or not.

Which writers (living or dead) do you feel have influenced you the most?

Visiting the Robert Frost Farm in Derry, New Hampshire, I stood whole minutes in front of the chair where Frost sat and wrote many early poems. I was just absorbing the atmosphere right there. At that moment, I didn’t realize it but I was composing a poem, “Robert Frost’s Chair,” which is in the new book. By the time we finished the tour, the poem was complete.

So Frost certainly an early influence. As were Shelley and Keats. Even T. S. Eliot and Allan Ginsburg. Later on Galway Kinnell, Philip Levine, Rilke, Anne Sexton, and Robert Bly became models to emulate, both for themes and for use of language. Over the years, I believe there are many of my poems that show and image, a phrase, a theme, even, that grew out of one of their poems.

Tell us a little bit about your new collection: what’s the significance of the title? Are there over-arching themes? What was the process of assembling it? Was is a project book?

The title of the new book was not the title in the original manuscript. The editor of Presa Press, Eric Greinke, with whom I’ve worked with on my previous book, telephoned me to accept the manuscript and to make suggestions, as any good editor should do. One suggestion was to title the book after the poem, “White Storm,” which he felt was the strongest in the collection and which he said conveyed the mood of the larger topic of all the poems combined: “the fragility of lives in the context of life going on,” as he describes it. I agree with that. I had assembled the individual poems from the many on file with this basically in mind.

I write individual poems as they arrive. Catalogue them by date. Then when I feel the urge to put a manuscript together, I’ll first list the poems by date of composition in a sort of Table of Contents with the newest poem first. In the process, I often discover a common theme or mood among different poems and if I feel strongly enough about it, I’ll group poems by these. If there are enough for a whole book, then that becomes the manuscript. If there are not, as is usually the case, I’ll determine if there are enough similarities to form a section of a book, several sections, and that can become a manuscript. In this new book, White Storm, some poems were brand new at the time, some a few years old, and a couple are decades old. These last, though often published in magazines, were just hanging around with no home other than some file, until I put this manuscript together and found that they fit in here. This is how I usually assemble a book and I like this process. It keeps me close to the poems.

Read an excerpt from his book here:

AGAINST DEATH

For weeks the birds chatter the treetops,

winging above the meadow,

and perched on roofs along the street.

Each its own song, its own necessity;

each an offering to the vaporous world.

Wordsworth said Coleridge talks

as a bird sings, he could not help it: it is

his nature, and all listened to his melodies,

enraptured. He, too, added voice to

the sonorous earth, an omnidirectional beat

thumping urgency against time’s pulse.

Robin sings to robin, finch to finch.

The beclouded poet sang to angels and devils

equally, and each replied in kind, by their natures,

with a wager of charged breath breathing

the hymns of articulated nature.

Long may the spirits fly in the riot of bird song

when the earth tilts toward abundance and beyond.

Long may the spirits incarnate the songs of birds

as the sun resonates its light through air.

Though the voiceless dead outnumber

those who sing, still, each bird has a song.

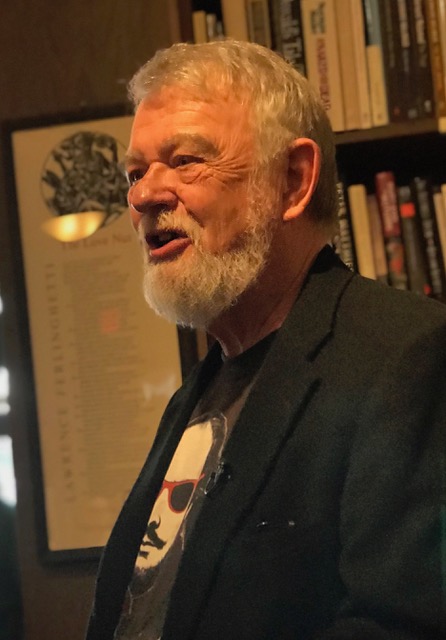

Gary Metras’s new book of poetry is White Storm (Presa Press 2018), with another book, Captive in the Here, due soon from Cervena Barva Press. The author of sixteen previous collections of poetry, his poems have appeared in America, The Common, Poetry, Poetry East, and Poetry Salzburg Review. A retired educator, he has taught middle school, high school, and college. He lives in Easthampton, Massachusetts, where he has recently been appointed the city’s first Poet Laureate. He is also the editor and letterpress printer of Adastra Press.