When did you first encounter poetry? How did you discover that you wanted to write poems?

I first encountered poetry in Mother Goose rhymes and children’s anthologies. When I was a child, my grandmother used to recite “The Owl and the Pussycat” by Edward Lear to me and my sister. My mother read us “The Highwayman” by Alfred Noyes. I still have a little pad of pink paper where I copied out “Full fathom five” from The Tempest and “Sea Fever” by John Masefield when I was eight years old. At the age of 16, I read Wallace Stevens’ poem, “The Snow Man.” The triple use of the word “nothing” in the last stanza made me want to write poetry.

Do you have a writing routine? A favorite time or place to write?

I start each day reading over what I worked on the previous day or previous few days, in order to get me back into the right mindset. I usually have several projects I am working on simultaneously; I put my effort where I have the energy. I don’t have a particular time or place that I prefer to write, although I prefer long, uninterrupted blocks of time. I am a social person but not when I am writing. For me, talking is antithetical to writing. If I have to talk when I am writing, it breaks my flow of concentration. I need solitude to write. Solitude can be found in a café full of strangers, but not in the family living room with everyone sitting around and the television on.

Where do your poems most often “come from”—an image, a sound, a phrase, an idea, or elsewhere?

Poems come from all of these—an image, a sound, a phrase, an idea. I find inspiration wherever I can. One cannot will inspiration to come, but one must allow oneself to be receptive enough to recognize it. It’s a certain kind of attention, a readiness. I think it gets harder and harder every day as our attentions are fragmented and scattered. We’re supposed to pay attention to so many things at once. We’re in touch with everything and everyone but ourselves. It’s hard to go deep, to concentrate. Some days my mind can’t seem to settle on anything. Yoga and meditation help me to create a welcoming space, a willingness to receive inspiration with a proper sense of awe.

Which writers (living or dead) have most influenced you?

Virginia Woolf’s novel, The Waves, inspired my novel, Fall Love. I already mentioned the effect Wallace Stevens’ poem, “The Snow Man,” had on me. I think that writers aren’t aware of their influences at the time that they are being influenced. I think that if one is aware of the influence, then it’s not really an influence. It might be a model. But influences are more mysterious and unconscious. One only knows in retrospect.

As a child, I had The Golden Book of Greek Myths. I vividly recall my shock when I first read the story of Oedipus. And the truth is, every time I read it, I still feel the shock. What a story! Writing doesn’t go any deeper than that. The Biblical story of Joseph is another one. The family is the basic human social structure, and our deepest conflicts and yearnings; our desire, terrors, and taboos, go back to it.

In a larger contest, The Iliad has never been surpassed as the great story of war and society and capricious fate. As Simone Weil write in her wonderful essay, “Its bitterness, for it springs from the subjections of the human spirit to force. This subjection is the common lot, although each spirit will bear it differently, in proportion to its own virtue. No one in the Iliad is spared by it, as no one on earth is.”

What excites you most about your new collection?

I was pleased to read what one reader, John Vanderslice, wrote on Goodreads:

“This collection really shows Whitehouse’s range, maybe more than any of her other collections. There’s a bit of everything in here: the deeply personal lyric, the persona poem, the historical poem, travel poems, reflections of pop television and celebrities, imagistic incantations of various physical phenomena, and more. I don’t know if I’ve ever read a collection in which the poet showed such mastery over a variety of topics and genres. It’s beautiful work, and like all of Whitehouse’s poetry it engages you emotionally without you ever feeling manipulated. She always respects both the reader and the subject matter. This is very honest, but carefully written and wonderfully smart stuff.”

The title, Outside from the Inside, comes from a letter that the sculptor Isamu Noguchi wrote to the photographer Man Ray in 1942, when he was interned in the Poston War Relocation Center in the Arizona desert. Noguchi was born to a Japanese father and American mother. During World War II, he volunteered to be interned with other Japanese-Americans, thinking that he could teach them arts and crafts and help to make their experience more useful and bearable. However, he found the conditions at Poston so dire that he immediately regretted his decision, but it took some time to secure his release. On a visit to the Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum in Long Island City, Queens, in February 2018, I noticed Noguchi’s letter in an exhibit case. Noguchi’s letter developed into my poem.

The first section in the book, “Tides of the Body,” grew out of my anatomy studies and interests in yoga and meditation. The book’s title, “Outside from the Inside,” can also refer to the body as a starting point for the exploration of the world.

Sample poem from Outside from the Inside

KOKO AND ROBIN

When Koko met Robin Williams,

she was in mourning for Michael,

a fellow gorilla and her life-long friend.

They’d grown up together

like brother and sister.

The smile she gave Robin

was her first in six months.

Koko recognized Robin

from the television shows

where he’d impersonated Mork,

an alien befriended by Mindy,

who helped him adjust to life on earth,

while, off camera, he’d chased her,

copping a feel. Mindy recalled, “I was

flashed, humped, bumped, grabbed.

He’d look at me real playful,

like a puppy, with those sparkly eyes,

and then he’d do it and run off.

And he could get away with it.”

In sign language

Koko asked Robin to tickle her,

and she tickled him back, laughing.

Baring her teeth in joy,

she played with him,

putting on his glasses,

picking his pockets.

She could have crushed him,

but she cradled him

in her strong hairy arms,

rocked him gently to and fro.

He felt himself relax,

inhaling her smell, matching

his breathing to hers.

She stroked his arms,

hairy for a human,

and stared into his eyes,

and he stared into hers.

Later, in interviews on talk shows

and in stand-up routines, Koko

was Robin’s comic fodder.

He mocked her lasciviousness,

as he construed it.

Yet, there was more:

“We shared something extraordinary,

awesome and unforgettable.”

Robin was Koko’s playmate, friend

for a day, a creature she had held

in her arms and rocked

like one of her kittens.

Consumed by illness and sadness,

years later, Robin took his own life.

Learning of his death,

Koko wept.

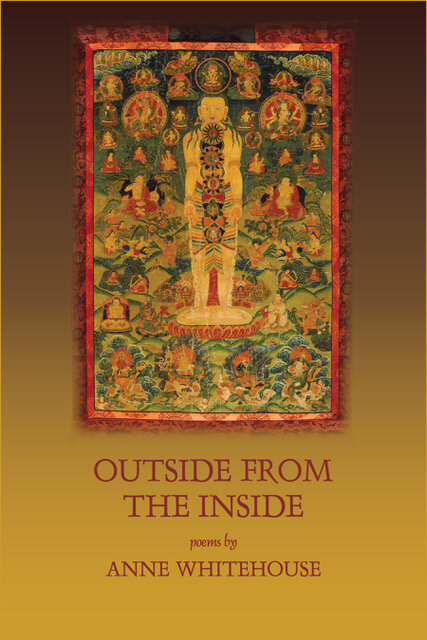

Purchase Outside from the Inside

Outside from the Inside is Anne Whitehouse’s third poetry collection published by Dos Madres Press, following The Refrain (2012) and Meteor Shower (2016). Her other poetry collections are Blessings and Curses (Poetic Matrix Press, 2009) and The Surveyor’s Hand (Compton Press, 1981), and two chapbooks, Bear in Mind and One Sunday Morning, from Finishing Line Press. She is the author of a novel, Fall Love, available in Spanish translation as Amigos y amantes, as well as short stories, essays, feature articles, and reviews. Born and raised in Birmingham, Alabama, she graduated from Harvard College and Columbia University and divides her time between New York City and Columbia County, New York.