a conversation between Lip Manegio and Bradley Trumpfheller

It seems fitting to begin an interview with the beginning of your book, so I wanted to ask about your epigraph, which is half critical text quote and half song lyric. That kind of mixing of the “high” with the “low” (to borrow language from Pop Art) comes up a lot in your work; is there a particular reason why you make that move?

Tiana Clark has spoken about how she sees and makes use of epigraphs, as being a way to acknowledge study and tradition: for individual poems & longer form works, the epigraph is a way to say “this is where I’m coming from,” which is a move I’m really invested in. So for this particular epigraph, I wanted to sorta collage the languages together, to find where Jaleh Mansoor’s scholarly book about Italian politics and art can blend into my favorite country song. It’s very much how my brain works, in some sense. Lots of things that don’t really go together going together. And it matters to me that people know where I’m speaking from, who I’m speaking with. In some ways, it’s not unlike sampling. Working to invite a tradition or an idea into the space of the poem, as a part of its architecture.

In that same vein, your work also seems highly concerned with language, and the ways it can be turned around and inside out to extract new meaning from familiar words. Do you think there’s a limit to what language can do, what meanings it can create? Or, perhaps, are there simply new realms of meaning we haven’t discovered yet?

That’s a hell of a question. I don’t think the options you offered are contradictory. I absolutely think there are limits, but the limits can be snuck past, disputed, pointed to. At least in terms of meaning-making, I think an ongoing project of poetry in English is to find those limits and contest them, to keep pushing the language past itself, to play around in the places it fails. A parallel project, which seems to me aligned with political struggle, is to invent a new language entirely. There’s a line from the communist poet Sean Bonney, where he’s talking about the ascendant far right in the West, and he says, “Our word for Evil is not their word for Evil. Our word for Death is not their word for Death.” We live in the late empire, you know? Every day you look around and some meathead fascist or democratic congressperson is using the same language in which I try to describe a bumblebee to justify and cover for their abjectly monstrous crimes. What do I—we—do with that? I don’t have an answer, really. Sometimes it seems like enough to make the poem fall apart.

If this book was a landscape painting, what would it look like?

See, this one’s hard because I want to just describe the landscape paintings I like! There would have to be a road, I think. This is such a road trip book. I use, obviously, lots of images of trees, flowers, animals, all the usual poetry clichés. But my hope is that I’m sort’f twisting the image a bit, bringing it four degrees to the left, putting it beside something it ought not to be beside. So the landscape blurs, doubles back on itself; there’s a cardinal next to an inside-out rose. I don’t know, I’m just kinda riffing now. Maybe it would just have a lot of fog. A road, some fog. And probably it’s nighttime.

The concept of miracles and the divine comes up a lot through this book. I was wondering if you could talk a little about that, or even about any small miracles you’ve experienced/are experiencing in your life?

You and I have talked about this before, so you know that I’m pretty much constantly thinking about God. Communism and God. It’s such a huge question, I’m not sure how to do it justice here. I was raised Protestant, in a few different traditions, mostly by my mom. It was, unsurprisingly, a big part of my connection w/ my family in the South. I think in the same way that you see a lot of repetition of images throughout the poems—dogwoods, porches, headlights—you can probably also trace through all the times that rapture comes up, or prayer, or my apparent favorite, heaven. Because so much of Reconstructions is coming from my life, the religious language slots easily into that framework; it’s something you can smuggle into your memory, and then live out in the poem.

More generally, though, making poems for me is totally bound up in how I think about my relationship to a divine, or at least my relationship to Christianity. The first poems I heard were the Psalms, for sure. Kaveh Akbar talks about one of the first known poets, a Sumerian priestess named Enheduanna, writing what is essentially a devotional song. But I don’t only mean in the more sort’f obviously literary ways. I was bullied in evangelical summer camps. I would stare at boys in church. My grandmother, a lesbian, was the most devout person I knew growing up. In a lot of ways, religion was the space I first became acquainted w/ queerness. I write from and with a lot of those early feelings of being queer, which, for me, is the feeling of being contradictory. I had to forge my own sort of relation to God and the Bible, within but also outside of what was given to me. Poems, maybe, are a cousin of that.

I know you’re going to hate this question but I have to ask: now that this project is out into the world, what are you up to now? Do you have anything on the horizon, or even just any good shows you’re binge watching?

I’m probably like terminally up to something. In terms of the right now right now, I’m just reading a lot. I’m grateful to have the kind of life currently that lends itself to there being a lot of books I haven’t read in my apartment. My roommates and I keep watching the movie Southland Tales—we’ve seen it about three times now. It’s like a fever dream. There’s a whole type of dumb movie from the 2000s that was billed as dystopian or sci-fi, where the premise was that the US turned into a militarized surveillance state. What a concept. Anyways, the movie maybe ends with a communist plot to transfigure Dwayne Johnson into Christ, or a hallucination that Justin Timberlake has after shooting up cold fusion? It’s unclear. Definitely a masterpiece.

I’m writing, and I’m also thinking a lot differently—or maybe, I’m thinking a lot more—about what projects can look like outside of publishing, outside of capitalism. It feels like we’re accelerating closer still to when this particular order falls apart, and we should maybe constantly be asking ourselves, even if only to affirm what we know, what does the next world have to do with poems?

What are three books (poetry or otherwise) that you think everyone should read?

Just to give a prelude to my three, I love this question. Which seems weird to say, but I remember so well when I would read poets answering this exact question in interviews and write all the books down, and then I would go to my library and check out just piles of poetry books at a time. That was a huge part of my education. That said, I don’t know what my desert island three would be. Here are three books that I don’t see talked about as often, which isn’t to say they have some special status of secrecy, just that I think they’re neat.

Extracting the Stone of Madness by Alejandra Pizarnik (translated by Yvette Siegert), one of those total top-of-my-head-taking-off reading experiences. Pizarnik is in that class w/ Dickinson for me, poets who really use silence as their material.

Craig Santos-Perez’s series from Unincorporated Territory, an unfinished book-across-books, is totally amazing. It’s a project that centers Guam & the people indigenous to the island in their ongoing struggle against US imperialism, and I think it’s a series that I’m always going to be returning to.

Fred Moten & Stefano Harney’s book The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study. It’s published with Minor Compositions, an anarchist press, and they’ve made the pdf available for free online if that’s your jam.

And, I’m getting a bonus one in here, I think everyone ought to read more work in translation! Ilya Kaminsky & Susan Harris edited The Ecco Anthology of International Poetry, which is a really remarkable survey of poets that don’t often get their due in the US. I also like Pierre Joris’ 4 volume series “Poems for the Millennium,” a kind of staggeringly comprehensive compendium of poems and commentary; two volumes I think are focused on 20th century modern & postmodern poetry, and the fourth is an anthology of written & oral literatures from North Africa.

A sample poem from Reconstructions:

Monument

I take off that winter like a sports bra

eye bright woman with the roman nose, aqueduct back arch

denim on denim on I take off my skirt

in minutes and in front of no one

what kind of my people is this

a glass wren sweeping feathers from the museum floor

how bone-rag, my time stutter

how three-windless, our nightjars & nightsticks

be serious

there was a boy, wolf’s bane, bright

dress, fifth grade, what was

his name, worm

moon with the twenty-sided hands

and the milk-eyed curtain what room

falling where we I wonder

is he still a boy was he a boy then the mountain

snow melts the mountain flowers, sea-birds sling

their diamonds, their syntax

my people, my exquisite corpse-breath

and pronoun and softly and sister

forgive me

I’m trying I’m trying I’m trying I’m trying

to write a history of us

without writing a history of us

being harmed

but when I think about that day

it is not your name I remember first

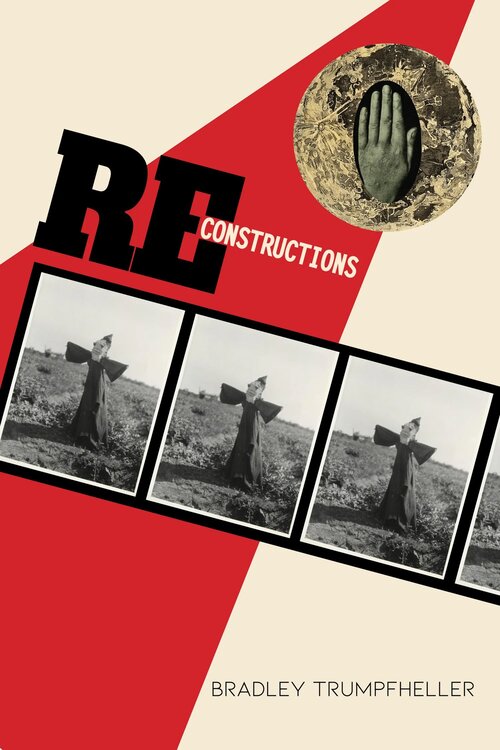

Purchase Reconstructions from Sibling Rivalry Press

Bradley Trumpfheller is a trans poet & bookseller, and the author of the chapbook Reconstructions (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2020). Their work has appeared in Poetry, The Nation, jubilat, Indiana Review, and elsewhere. They have received fellowships from the Michener Center and the MacDowell Colony, and currently co-edit the website Divedapper with Nabila Lovelace.