When did you first encounter poetry? How did you discover that you wanted to write poems?

As a Haitian-born writer, storytelling is something ingrained in my Caribbean DNA and as such I was always interested in telling stories. However, as most Caribbean children can attest to, you only spoke when spoken to, so I couldn’t contribute my thoughts freely and had no place to turn to other than writing. I was also a really shy kid and found the page to be a place where I could be myself without fear of judgment or censorship. However, I didn’t start out writing poetry—in elementary school, I mostly wrote scripts. Poetry came a bit later. I believe poetry happens to a poet long before they ever write it, and it was not until junior high school that poetry found me.

In Tiana Clark’s masterful book, I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood, she includes a line by Roger Reeves which states “Even the trees must perform sorrow.” I think that’s as good of a line as any to start the conversation about how I came to poetry. I was gazing out of the window on a very wet and cold day. It had been raining all morning and my mood was as dreary as the weather. I noticed rainwater cascading down a tree in a way that appeared to be a stream of tears. For a few minutes, I mused on whether the tree was crying because it was sad. And then I began to wonder if the tree was crying because it was sad or because it knew I was sad but couldn’t cry my own tears. I knew I had arrived at something new that day and even though I didn’t necessarily know it was poetry, I wrote what would be the beginning of a first poem. Poetry has been with me ever since.

Do you have a writing routine? A favorite time or place to write?

Due to my rigorous teaching schedule and having two young boys who require my attention, a writing routine is tough to establish. The type of space necessary within one’s mind to be able to enjoy the reception of words is not often available to me. As a result, I often read and write in spurts. Because writing often begins and ends when we least expect it, a writer must surrender themselves to the writing process and be ready to write. Full surrender requires acceptance of the moments when the pen or keyboard are constantly at work and also the half complete sheet or blinking cursor. The moments when we pause or have come to a full stop are as important to a piece as when we are writing. Which is to say, sometimes interruptions can be a writer’s best friend.

This is your debut full length project; was there a certain moment where you realized that this needed more space than a chapbook allows? How did you know when it was finished?

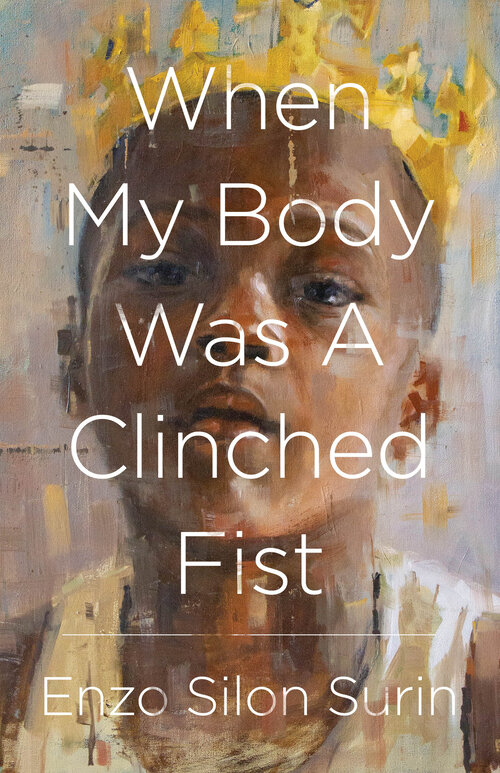

When My Body Was A Clinched Fist was always a full-length manuscript because there was never any shortage of material. At some point, I needed to cut down on the number of poems in the book because there were more than enough experiences to tap into. I cut out quite a few but a final round of revisions led to even more poems, including the very last poem in the book. I thought the revision process would never end but once I added the new poems, the manuscript felt complete. It’s not easy to know when something is finished, especially with poetry, but with this book I put everything I had into every single poem.

What are some themes or images that you found yourself returning to throughout this project? Did you set out intending to write around those themes, or did it happen organically?

Interestingly enough, the metaphor of the clinched fist was something that was so deeply embedded in every poem that I didn’t notice it until the last few years of revising the manuscript. It was definitely an organic experience as I wrote the poems, but it was a conscious decision to change a few of the titles in the manuscript to include the word fist. When reading the manuscript before sending it out, it became quite clear that every single poem addressed an experience that contributed to the body being a clinched fist, where any group of five poems represented a fist.

What is a book or author who has greatly influenced your own writing style?

My writing style has been inspired by so many literary contributors that to name one is quite difficult. In addition, I have been greatly influenced by music—Haitian Konpa, rap, folk and jazz, to name a few—so this list would be quite long. However, I would say one book that had a profound influence on my writing style the past several years is Cahier d’un Retour au Pays Natal, translated as Notebook of a Return to the Native Land, by the late Martinican writer Aimé Césaire. His writing style gave me permission to be myself and freed me to tap into the cadence of my own Caribbean roots. His ability to manipulate language, have fun with it, and consistently turn common phrases into idiomatic syncopation is remarkable.

Sample poem from When My Body Was a Clinched Fist:

In A Fisted Universe

Would have thought we were trained

for the shots we took—fists tossed

into the blind bend of neck-n-shoulder

where truth held more misses than hits—

most of which was more show than blow.

Sometimes, as if on cue: a spot broke open

in the crowd amidst drawl and grimace—

and the withdrawn drew their card into

the dark matter of an ever after—triumph

or defeat, no one ever cried, as if the body

only attended to the tear and break and not

to tears. Most of these bouts, staged in empty

school lots—fists flaring their stellar remnants—

begat not one bona fide winner—fight within

as bitter as any in the ring. And the one

thing that always survived were lies told

about whose fists were hindmost—not

how easily hearts, under guard, went into

flip mode over a fresh pair of white sneakers,

and how some were eager to pledge homage to

a posse—didn’t matter the cause or if one really

believed in the push of fists over bodies—one day

you’d be next. And some years from this moment,

the sound of something breaking; some poor boy’s

plea, will awaken lessons learned in science class,

about sound travel in space—myths of how

one can witness the destruction of the world

without a single sound—how one can wail, wail,

wail, and no one’d be able to hear it. But you

know this to be claptrap—in space or back lot,

you can always hear the blare of your own ruin.

Purchase When My Body Was a Clinched Fist

Enzo Silon Surin, Haitian-born poet, educator, publisher and social advocate, is the author of When My Body Was A Clinched Fist (Black Lawrence Press, July 2020), and the chapbooks, A Letter of Resignation: An AmericanLibretto (2017) and Higher Ground. He is a PEN New England Celebrated New Voice in Poetry, the recipient of a Brother Thomas Fellowship from The Boston Foundation and a 2020 Denis Diderot [A-i-R] Grant as an Artist-in-Residence at Chateau d’Orquevaux in Orquevaux, France. He holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Lesley University and is currently Professor of English at Bunker Hill Community College and founding editor and publisher at Central Square Press.