When did you first encounter poetry? How did you discover that you wanted to write poems?

I first “discovered” poetry when I was a senior in high school, although I remember my mother reading me poems when I was a child. I had a great teacher, who’ stop at nothing to get us interested. I can still see him jumping on his desk to recite “Is this a dagger that I see before me?” The first poems that I found thrilling were Frost’s “Fire and Ice”—it was amazing to me that a poem could actually mean something, and “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” which I found incredibly beautiful and moving. So of course I wanted to write poems too. But since I knew I could never write anything as beautiful as Keats, I wrote a poem called “Moonlight and Garbage.” I got a little more serious (and pretentious) in college. But I think my good poems are closer to “Moonlight and Garbage” than anything I wrote in college.

Do you have a writing routine? A favorite time or place to write? Where do your poems most often come from—an image, a sound, a phrase, an idea?

My writing “routine” is to resist writing a poem as long as possible, until the poem won’t let me go. And then I’ll take every waking minute I’m not obligated to do something else to work on the poem. In that respect, I’m not a good role model for my students. These days, I depend more on my computer to work on revisions, so poems get finished in my study, but they can get started anywhere.

I think that was partly an answer to your next question. I guess the answer is closer to “an idea”—something that comes into my mind and insists it has to be written about. I’ve just begun to discover in the past few years that poems can come to me as responses to outside stimuli—challenges from various sources to write a poem. I didn’t think I could do that, but at least four poems in Little Kisses were responses to challenges.

Which writers (living or dead) do you feel have influenced you the most?

Influences? That’s so hard to say. The writers I hope have influenced me most are Keats, Robert Lowell, and Elizabeth Bishop. Not because my poems are anything like theirs, but because they were so dedicated to writing poems, and dedicated to writing their own poems. In terms of which writers have influenced my writing most, I’d probably have to say Chaucer, Browning, and Frost, because they wrote poems in the voices of other characters and that’s often what I’m trying to do in my own poems. And maybe especially Chaucer because he had such a great sense of humor, and I like serious poems that have some element of comedy. Some Bishop poems have incredibly funny passages.

Tell us a little bit about your new collection: what’s the significance of the title? are there over-arching themes? what was the process of assembling it? was is a project book?

The hardest thing about being a poet is putting a collection of poems together. It took forever (something like 15 years) to put this new book together, but that was partly because I was doing a lot of editorial work, putting together two big collections of Bishop’s work, which was incredibly time-consuming. It was important for me to do that, to repay her kindness to me.

The title of this new book comes from the poem about my mother, which includes a memory of her singing one of her favorite songs to me when I was a little boy, a song from the 1920s called “Gimme a Little Kiss, Will Ya Huh?” Those “little kisses” were like Wordsworth’s “spots of time,” those memories of almost accidental moments that somehow stay with you for the rest of your life. I knew when I wrote that poem that it would be the title poem, because aren’t all poems “little kisses”—gifts to the poet—ways of preserving feelings or moments from the past or even just thoughts that get preserved in a poem.

And because I never know from which direction a poem is coming at me from, it’s hard for me—certainly at first—to see any kind of pattern. Gradually that pattern, if you’re lucky, begins to emerge. Little Kisses fell into sections—first elegies of a sort, for my mother, for a grandmother I never knew (which means a lament for a whole part of my origins), and for someone who died too soon. Then there are poems in various ways about art, about retrieving what’s been lost. Then a sequence of shorter poems that are in some ways more playful, among them those “challenges,” which are also serious but less obviously so (like being challenged to write a new poem with the title “Howl”).

Then there’s a section of translations—from a wonderful Brazilian poet (I know some Portuguese, having been to Brazil in the process of my work on Elizabeth Bishop, who lived there for many years) and from a Ukrainian poet (I know no Ukrainian—my translation was commissioned by an editor who offered poets a literal translation to work from). The original poems are very different from my own poems in English, and yet in the process of translating them, they kind of also become my poems. One of my favorite lines in the book is from the Ukrainian poet Viktor Neborak’s poem “Fish”: “No fish is an island.”

The last section of “Little Kisses” is a series of poems that come mainly from traveling, leaving home, and the various ways we try to find our way home. It begins with a prose poem inspired by a cosmic collage painting by Gerry Bergstein called If You Lived Here You’d Be Home Now. Two poems in this section are about the mysterious disappearance of my oldest friend. The last poem, “Jerry Garcia in a Somerville Parking Lot,” is the closest to home, and includes the line “how little it takes to restore his / affection for the city”—ending with a kind of tentative coming home.

JERRY GARCIA IN A SOMERVILLE PARKING LOT

Past midnight, a man in his late 60s, tall, with long

gray hair and a bushy gray (almost white) beard,

returns to the side street public parking lot

where he’d left his car. It’s hot, and dark, and the lot

is unlit. At the far end he can make out two men

smoking, leaning against the car right next to his.

Alone and apprehensive, he starts across the lot, and

soon catches a whiff of what they’re smoking.

Suddenly one of them asks:

“Want to hear a joke?”

Startled, he hesitates, but obliges. “Sure,” he says.

“What’s the joke?” “OK: What do you call a woman

with only one leg?” “I don’t know,” he plays along.

“What do you call a woman with only one leg?”

“Eileen.”

It takes him a second, he almost groans, and then

he begins to laugh.

“Want a drag?” the guy asks. He’s just a kid

(the other one never says a word). “No, no thanks,”

the man answers, “I can inhale from here.”

This time it’s the kid who laughs. “OK. I only asked

because you look like Jerry Garcia.

—Have a nice night!”

“You too,” the man answers, unlocking his car.

“Thanks.” And all the way home, he keeps chuckling

at lucky escapes, wildly mistaken identities, sweet

dumb jokes (how little it takes to restore his

affection for the city), and at least for the moment

gratefully alive, can’t stop laughing—or laughing at

himself for laughing—at his latest temporary reprieve.

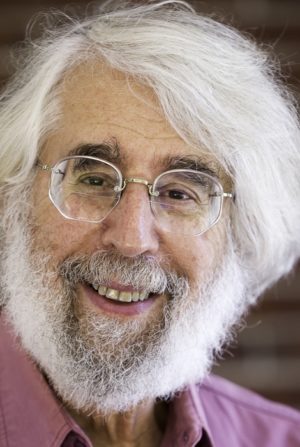

Lloyd Schwartz’s poetry collections include These People (1981), Goodnight, Grace (1992),Cairo Traffic (2000), and Little Kisses (2017). His poems have been selected for the Pushcart Prize, The Best American Poetry, and The Best of the Best American Poetry. A leading authority on the American poet Elizabeth Bishop, he is co-editor of the Library of America’s Elizabeth Bishop: Poems, Prose, & Letters (2008)and editor of the centennial edition of Bishop’s Prose (FSG, 2011). A multi-prize-winning critic, he was awarded the 1994 Pulitzer Prize for Criticism for his columns on music in The Boston Phoenix. He is currently the classical music critic for National Public Radio’s Fresh Air, contributing arts critic for WBUR’s the ARTery, and senior editor for New York Arts. He’s the Frederick S. Troy Professor of English and teaches in the Creative Writing MFA Program at the University of Massachusetts Boston.