When did you first encounter poetry? How did you discover that you wanted to write poems?

I’ve been a reader of poetry for my entire life. My parents read to me, but I was an early reader too, so I was able to take in A. A. Milne and Robert Louis Stevenson, for example, before I started school. My poetry-reading habit intensified in the early 1990s, as I began to have more poets as friends and attended more readings. That’s when I started reading in multiple books of poetry every day. Since retirement, this has accelerated further, to include more journals and anthologies.

I come late to writing poems myself, as an ongoing activity. For much of my life, I’d feel an impulse to write something like a poem about every two or five years. So I did, tucked it away and forgot about it. (Never mind my high-school political doggerel!) It’s only for about the last dozen years that I’ve pursued this deliberately. This isn’t a dramatic story. Out of curiosity, I took a couple of one-off poetry workshops in middle age and discovered that there might be more for me there. The threshold event was a one-weekend workshop with Jane Hirshfield, at Zen Mountain Monastery in the Catskills. None of the three poems that came out of that workshop are worth retrieving, but they were real enough to me then.

My first real affirmation took place early in the 2010s, when I was a librarian at Curry College. I was invited to join an informal faculty creative-writing group. I remember that when I first brought poems to the group—clumsy productions—my peers responded to them as if they were, indeed, poems! Not great poems, barely good ones, but worth critiquing as poems. This was quietly but truly encouraging.

Do you have a writing routine? A favorite time or place to write?

If only! I typically write (revise/send out work/do this interview/etc.) mid-to-late mornings, most every day. Some days this will spill over into the afternoon or come back up later in the day. I do not have the “sacred space” that many poets treasure, but I also don’t seem to crave it. I most often write at the kitchen table, because the view out the window to the neighboring city backyards is congenial. Many poets reserve the first hours of the day for writing, but that’s my dedicated poetry-reading with first cup of coffee time. I would resist giving that up.

Where do your poems most often “come from”—an image, a sound, a phrase, an idea?

This varies a lot, in part because I seem to have different “voices”—or better, that my poems have different voices. Bend in the Stair is concentrated on family stories, the impetus for the collection being the death of my father in 2018. But there are also poems of daily, present life, two “golden shovel” poems, and “AutoParallel Obit,” based on found material. I did a web search to see what the world might tell me about “David P. Miller.” It turns out that he’s lived and died many times.

“AutoParallel Obit” is like other poems of mine that might be considered experimental—though that term is vague—in that it takes found language itself as source material. I have a great interest in this, though this book’s focus is elsewhere. I’ve also written a fair amount of ekphrastic poetry, and poems in traditional forms including pantoums and sestinas. I want to focus on each poem as its own entity, with its own impulses, diction, and form (there being no truly formless poems). Perhaps I neighbor Emerson when it comes to consistency, even Whitman with self-contradiction! That’s aspirational, hmm?

Which writers (living or dead) have influenced you the most?

I have a couple of different answers. Aside from Milne and Stevenson, when I was a child I got into Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear very early. They helped develop the sense I already had that ordinary life wasn’t entirely what it claimed to be. I didn’t have a notion of surrealism, but you don’t need to be an art historian to know that consensus-reality is always nudging up against other worlds. The concept of “nonsense poetry” isn’t truly adequate to describe this. Humor was the key to this door, but not the endpoint.

Further than that, these writers gave me an early sense of the materiality of language, its “mouth feel” as we might call it. The simple fact is, it’s intensely pleasurable to let “the vorpal blade went snicker-snack” activate your body from the vocal cavity out. As, later on, John Lennon’s “semolina pilchard climbing up the Eiffel Tower” made me ecstatic. Again, “nonsense” is a weak concept in this regard. Engagement with any kind of language is, I am sure, inevitably psychophysical. It’s that this is more evident with non-status-quo language.

That’s one answer. The second is about poets who I read as an adult. It’s more difficult because I’m reading all the time. I rarely reread individual books of poems because I always want more, so I don’t really have core influences. But let’s imagine a terrain bounded by, for example, Tracy K. Smith, Donald Hall, Emily Dickinson, Eileen Myles, Jackson Mac Low, and Afaa Michael Weaver. I have many other possible terrains.

What excites you most about your new collection?

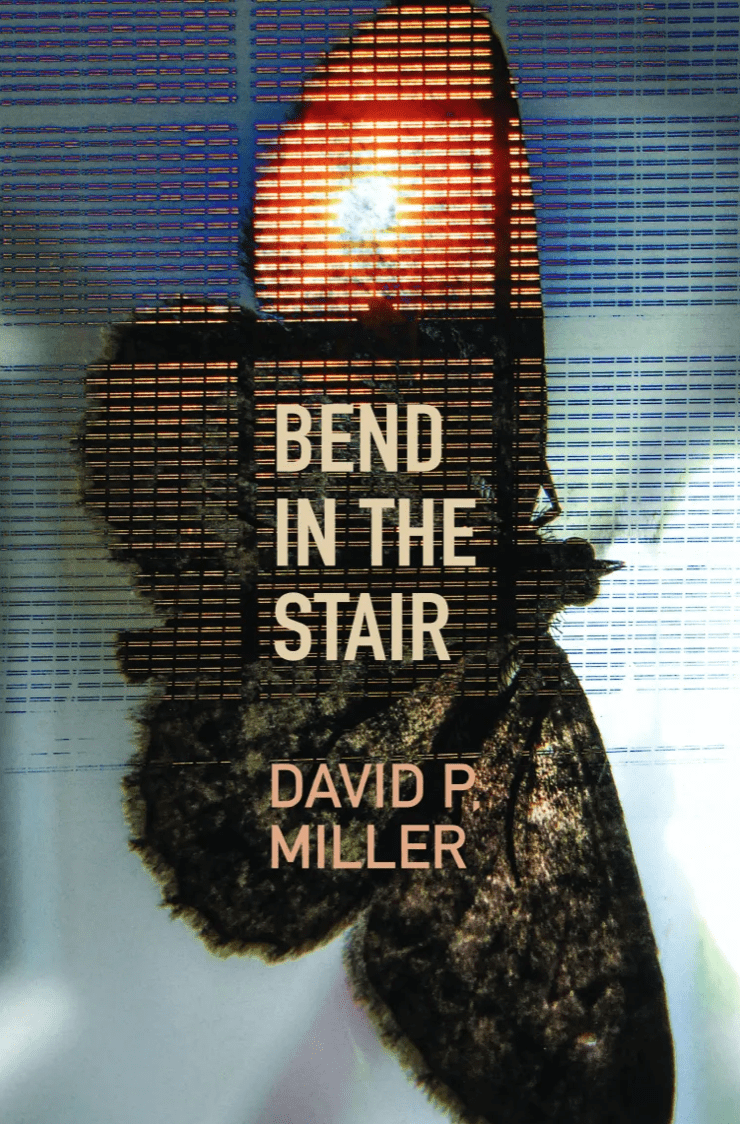

I’m most excited by the fact that the book exists! Such a thing seemed like a remote possibility only a few years ago. I’m also very happy with the book as the product of collaboration. Of course, it’s my name on the title page, but it wouldn’t exist without my publisher Eileen Cleary, primary editor Lisa Sullivan, book designer Martha McCullough, and the cover artist, my wife, Jane Wiley. Coming as I do from performing arts, I naturally have to call out the team.

The title comes from a phrase in one of the poems. The book doesn’t have a “title poem.” I’m interested in book titles as Easter eggs, to be discovered by an alert reader – who can consider its significance for herself.

As for themes, I’ve mentioned my father’s death, which happened within days of my retirement. Bend in the Stair is not a project book, strictly speaking. But the sudden shift from oldest child to oldest member of my birth family catalyzed a good deal of writing and aroused a matrix in which poems on other subjects found a place. I hope that, overall, readers with a range of life experiences will find it engaging.

The Story So Far

David P. Miller

You made it past the kitchen cockroaches,

some play-acted fumbles at adultery.

Past the DOA M.A. that tripped you

down the garden path to part-time

jobs in slapdash fragments. You made it

past the divorce, then five years

in a gnat-cloud of stillborn lusts.

Past the landlord lineup, a cul-de-sac of bosses.

You even made it past a profession, Professor.

You survived your mother’s vacant decay,

sat with your father’s final heartbeat.

And you haven’t died yet. In the sequel,

you junk their address labels, abort his phone bill,

waste-paper their church programs,

adopt his litter of bookmarks.

The proof you’re still alive is your first sighting

of your mother’s high school pictures

with her love note in his sock drawer.

Purchase Bend in the Stair

David P. Miller’s collection, Sprawled Asleep, was published by Nixes Mate Books in 2019. His chapbook, The Afterimages, was published by Červená Barva Press in 2014. “Add One Father to Earth,” included in Bend in the Stair, was awarded an Honorable Mention by Robert Pinsky for the New England Poetry Club’s 2019 Samuel Washington Allen Prize competition. With a background in experimental theater and performance before turning to poetry, David was a member of the multidisciplinary Mobius Artists Group of Boston for 25 years. He was a librarian at Curry College in Massachusetts, from which he retired in June 2018. He and his wife, the visual artist Jane Wiley, live in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston.