When did you first encounter poetry? How did you discover that you wanted to write poems?

Growing up in a small New Hampshire town, I found solace in many places- the woods, the estuary, the railroad tracks- but always seemed to find myself returning to the same spot: nose-deep in a book. For me, it was the opposite of escapism; when I read a book, especially a book of poetry, I felt closest to myself. While I was outgoing and scrappy, I struggled with expressing my inner thoughts, those sprouting emotions that left me speechless. My mother, the compassion soul she is, noticed my poetry-seeking tendencies and introduced me to Robert Frost, Emily Dickinson, and E.E. Cummings. I was amazed how poetry could pull even the most stubborn words from my mouth and place them fearlessly on a page.

I didn’t quite understand what poetry meant to me until I discovered clinical medicine. As an undergraduate student in Boston, I was given the privilege of volunteering with neurology patients at a teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. I would visit the hospital every chance I could- on weekends, in snowstorms, on my birthday- and became obsessed. Every time I stepped out of the hospital doors, a wave of joy would rush over me, followed by a tangible weight. Here I’d found this sacred realm, this beautiful world, but one that kept me up at night. I knew patients in unbearable pain, sent to hospice, who would never speak, or who passed away. Seeking comfort and meditation, poetry returned to my life. Writing medical poetry created a harmonious relationship with my love for medicine and my itch to write; it brought everything full circle.

Do you have a writing routine? A favorite time or place to write?

Usually my routine consists of letting a moment in medicine play out and observing it with humility and patience. It could be a bedside interaction between a physician and patient, or a Level 1 Code Trauma. Medicine, much like writing, demands you open yourself up to everything you need to feel in order to help someone else. It is only after those moments as a healthcare worker when my inner poet kicks in.

The poem will take anywhere from one day to several weeks to reveal itself, almost always catching me off guard. It will hit me out of the blue, when I’m lifting at the gym, or biking along the river, or riding at the skatepark, and I have to scramble to my nearest notebook to catch it. For me, science training came easy, but poetry is a much more difficult entity to tackle. My poetry methods aren’t technically based or stylistically mature, but I have come to enjoy the process of letting a poem spontaneously show itself when it’s ready. When it comes to my poetry methods, I’ve come to accept that not everything I do needs to boil down to a science.

Where do your poems most often come from—an image, a sound, a phrase, an idea?

My poetry is almost entirely fueled by clinical moments. For the past four years, I’ve had the privilege of exploring diverse clinical settings and found every space elicits different variations of the same awe. The neurology inpatient unit is bursting with moments of subtly, like the stroke survivor who couldn’t clean the cracker crumbs off her face. Then there is the OR, which is filled with more visceral elements, like the female resident who took a moment of silence before each surgery. Currently, I work as a medical scribe in an Emergency Department, which is a front-row seat to both human suffering and human joy. These places are different landscapes of the same world, and I use poetry to celebrate them.

Which writers (living or dead) do you feel have influenced you the most?

A dear friend from university gave me a book for my 22nd birthday, titled “Poetry in Medicine: An Anthology of Poems About Doctors, Patients, Illness and Healing”. In its pages, I uncovered some of my favorite writers, including physician-poet Rafael Campo. Dr. Campo was an internist where I was working at the time, and I became captivated by his story as a gay Hispanic doctor. As a young lesbian, Dr. Campo’s mission to treat patients as a physician and advocate for LGBT+ voices as a poet was moving. This was something I had dreamt of but didn’t think was possible until I read his work.

Through Dr. Campo’s writing, I also became acquainted with the other legends, especially William Carlos Williams, John Keats, and Suzanne Koven. I have particularly loved learning from Dr. Koven, an internist at Massachusetts General Hospital and its first writer in residence, who I turn to often in times of doubt and conflict. Her narrative medicine pieces are filled with a fierce commitment to patients and to self, tackling mountainous issues in medicine with unparalleled grace.

Through this journey, I have also connected with my mentors and teachers, Neal Whitman and Stuart Blazer. Neal, the Haiku editor of Pulse: Voices from the heart of medicine, was the first to teach me how to pack a punch in every word of a poem. He has shown me a great deal about the therapeutic powers of storytelling and has been a huge influence on my stylistic approaches. Stuart, a Rhode Island-based poet, changed the game for me. After reading Aqua Firma, I was hungry to understand the technical aspects of poetry and he graciously cultivated a creative space for me to experiment with my writing.

Tell us a little bit about your new collection: what’s the significance of the title? are there over-arching themes? what was the process of assembling it? was is a project book? etc.

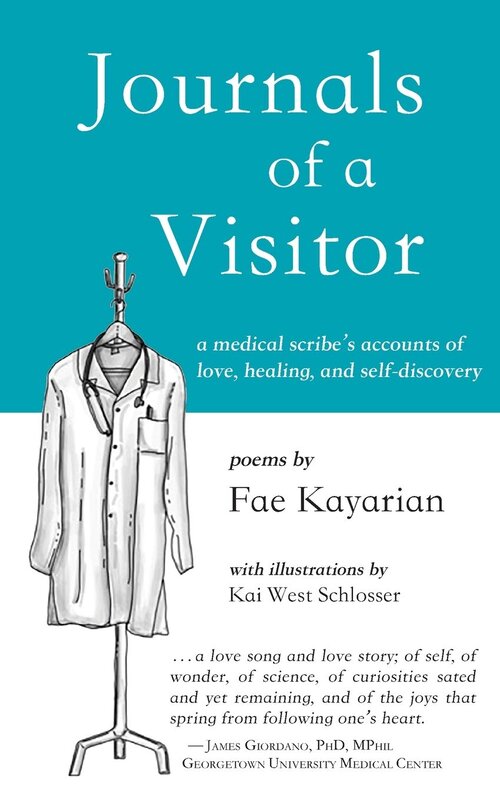

Using medicine as a lens for storytelling, Journals of a Visitor: A Medical Scribe’s Accounts of Love, Healing and Self-discovery honors the experiences that breathe meaning into our lives and celebrates the therapeutic power of writing one’s own narrative. The book shares my coming-of-age story as a young, queer woman in medicine, and the patient narratives that weaved their way into the fabric of this journey. Based on true events at Harvard Medical School, this collection of poetry discusses topics of healing, illness, mortality, love and self-discovery, told through the point-of-view of an aspiring physician. It has been an incredible honor and privilege to be able to write this book- a love story of medicine, of science and of self.

Sample poem from Journals of a Visitor:

Untitled

I was in the room, but where were you?

The attending was there,

the residents were all accounted for.

Every trauma nurse was present,

the other students and I stood in the doorway.

And the blood, the blood was there too.

The blood was joined by a heavy, haunting smell,

a smell that soaked the fabric of our scrubs

and weaved its way into our skin.

There was red and grief,

and courage and defeat.

We were all there, all present for the code.

We were in the room, but where were you?

God, where were you?

You were the only one who didn’t show up.*

*Inspired by “War”, a poem by Helen G. Nakshian, 1935.

Purchase Journals of a Visitor

Fae Kayarian resides in Boston, Massachusetts, where she is a medical scribe, researcher, writer and poet. As an undergraduate at Northeastern University, Kayarian began writing medical poetry after founding a volunteer program at Harvard Medical School. Her obsession with narrative medicine officially took off when she became a clinical researcher, neurosurgery student-observer, and an emergency department medical scribe. Thus, her book of poetry, Journals of a Visitor was born. While her story is, so far, unwritten, Kayarian aspires to become a physician and to continue engaging in medical humanities initiatives that celebrate science, medicine, and love.