When did you first encounter poetry? How did you discover you wanted to write poems?

It began with Bob Dylan’s lyrics at the age of thirteen and then Charles Bukowski was the first poet I read—no, no— I could “relate to” somehow. From there, my whole high school career I read the Beat Generation. That was all who existed for me. I had already been keeping a journal for forever and I wanted the ability to play with language, and so I began reworking my entries into poems, or what I thought were poems. All I knew was I had to write, it was the only way I could understand myself.

Do you have a writing routine? A favorite time or place to write?

My best writing is in the morning when I am still waking up and on my way to being fully present. I love writing with other writers, we riff off one another. I attend a freewrite group. Usually we pick writing prompts from magazines, The Book of Knowledge, fiction/non-fiction and spill our guts to the page for 4 minutes 19 seconds (that time was passed down to us by my mentor, no questions asked) without putting down our pens. And then we share what we wrote. Now we may have just a bunch of nothings, but sometimes you have the makings of a poem, something you never even thought about before. You see, I don’t choose what I write, it just enters out of somewhere inside me, all by happenstance.

Tell us a little bit about your new collection: what’s the significance of the title?

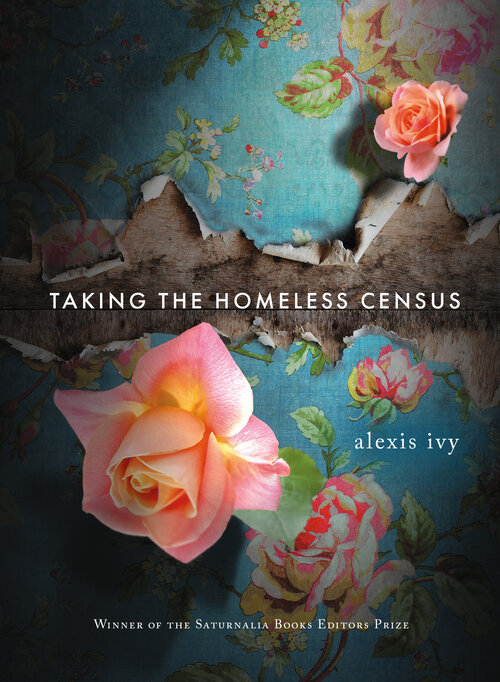

Taking the Homeless Census, my second poetry collection, begins with a crown of sonnets concerning my work with the homeless community. This sonnet sequence captures the vulnerable moments of shared humanity. The remaining poems are a heartfelt response to the crown, splintering my relationship with my lifework while questioning the definition of home. These poems are trying to find beauty in the wounds. These poems allow readers touch the untouchable.

Taking the Homeless Census—this title was my title before I even had a career in homeless services. I had this title before I ever even took the annual homeless census. Now, I am one of the leaders of the Cambridge/Somerville Census and have participated and coordinated the census three times. Part of the census is to define what makes a person homeless. This definition is way more complicated for a poet; I cannot accept the textbook definition. I imagined what it would be like to take the census— I took my own census where I tried to define what home was as I was making a home in this world.

What was the process of assembling it?

It wasn’t my intention to write a crown of sonnets for the book, it is just what ended up happening. I wrote a few sonnets and then it became my project. I already had 30+ poems for the book, but once I completed the crown, which is a focus on my work in homeless services, the whole book transcended into a response to those sonnets. The crown had been the second chapter for a year, then I came to understand that the book suffers when arranged in chronological order. I needed to tell the reader where I am presently and then show in the remaining chapter how I got there.

Which writers (living or dead) do you feel have influenced you the most?

Eliot, Frost, Millay, Neruda, Gwendoyn Brooks, C.K. Williams, Barbara Helfgott Hyett, Natasha Trethewey, Kim Adonizzio, Natalie Diaz, Eduardo Corral, and Brittany Perham.

What are you working on now that your book is out in the world?

I am working on a few new things—translating the Spanish poet, Rafael Juárez. This process has taught me so much about sentence structure and the search for the right language to serve a poem’s meaning, as I am the translator and do not get to choose what the poem means. How humbling.

Then, there is the short story I have never quite finished but on route to finishing now. I just got to the place where my story needs fiction instead of truth and I’m learning that fiction may just be another way to truth.

Also, and as always, I am writing a new collection of poetry. Of course, I am still playing with form, just wrote a few poems using a new form called a golden shovel, invented by Terrance Hayes. Look it up, it’s a form with freedoms and it’s made me a better poet. As for subject matter—I am still figuring out what I am trying to say and loving every moment of it.

A sample poem from Taking the Homeless Census:

OUTREACH

Winter finds him on the train station floor

sleeping in the shelter blanket I gave him,

beneath the Alewife sign in bedlam’s lower

weather. I bring him socks, toiletries, bring him

a woolen hat. I show up. I always come here

kneel beside him— his shelter, his prayer, his street,

my knees kiss the tiles to face him. Can he hear

the worry in my voice? His eyes are worried

blue. Doesn’t he want to live just a little longer?

Most of him seems mostly warm. Midnight, I’m in the

station, it’s perfectly dead, no passengers.

He wakes to sleep, and sleeps so I’ll wake him.

I’m his moonlight and sun. The stars I spare.

My smokes all smoked. Lost or broken. Or shared.

Purchase Taking the Homeless Census

Alexis Ivy is a 2018 recipient of the Massachusetts Cultural Council Fellowship in Poetry. She is the author of Romance with Small-Time Crooks (BlazeVOX [books], 2013), and Taking the Homeless Census (Saturnalia Books, 2020) which won the 2018 Saturnalia Editors Prize. A Boston native, her poems have been displayed in City Hall and featured by Mass Poetry aboard the red line subway. Her poems have recently appeared in Saranac Review, Poet Lore and Sugar House Review. She works as an advocate for the homeless in Cambridge, and teaches in the PoemWorks community.