When did you first encounter poetry? How did you discover that you wanted to write poems?

It was the summer I turned eleven. I discovered T.S. Eliot’s collected poems on my mother’s bookshelf, along with Emily Dickinson’s work. I was blown away by how you could use words so evocatively, though at the time I clearly didn’t fully realize what either poet was doing with language. My love of words began much earlier though, around the age of four: my parents were grad students, my older sister learning to read and write, I remember feeling excluded from a secret world everyone around me was privy to- I wanted in on the fun and asked my mother to teach me the alphabet. I just ran with it and taught myself how to read began composing my own song lyrics. I think poetry was the natural trajectory for me, I wrote my first poem the year I turned twelve- “flight of the swans”, a poem both terrible and glorious, insipid yet tonally lovely. The process was so gratifying, I knew then that writing poetry was going to be something I was always going to do.

Do you have a writing routine? A favorite time or place to write?

I used to burn the midnight oils but Covid-19 has been a game-changer. Now I like to write in the afternoons. My writing routine tends to shift every few years but there are some constants to it too, I do a daily 25-20 minute free-write, keep word lists, an imagery list, you know, the standard poet practices. When drafting a new poem for example I get a little obsessed, I’ll spend every free moment with it, mulling over lineation or verb choice, until I feel I can finally put it down, though to be honest I can be lax about keeping up with the lists at times.

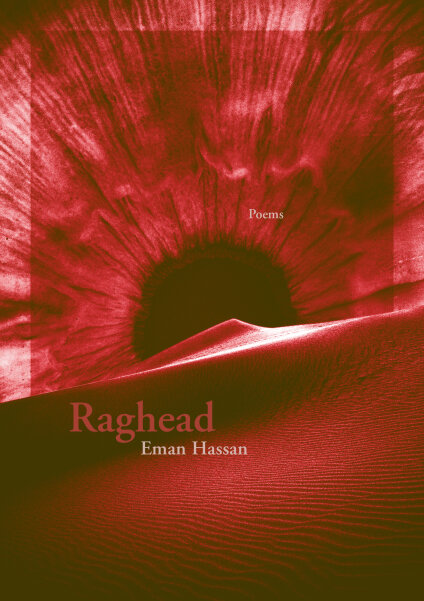

The title of the book is, obviously, very evocative. What made you decide to use that as the name of the collection?

I saw that it was the right title and went with it. Since one of things the collection seeks to do is to peel back the layers of preconceived notions we have about ‘other’ subjectivity constructs (as well as explore how war, capitalism, and environmentalism intersect), using the pejorative, was an opening into this self/other witnessing that takes place in many of the poem’s attempts to transform the dialogue into one of a self/self. Also, the title poem, “Raghead”, tries to humanize that enigmatic Gulf Arab figure through a glimpse into a father/daughter relationship and gender performance. In this poem, the negative associations of being a ‘raghead’ are turned on its head as this cultural headcloth becomes a figure for imaginary play as the speaker of the poem thinks about sexual identity. It becomes an object that is loved and revered rather than something derogatory. Many of the poems explore different aspects of identity but the main impetus focuses on how we regard and accept each other in our respective identities— ‘Raghead’ seemed to be the right symbolic fit.

A conversation I find myself having with a lot of my poet friends is how to take care of ourselves when we are writing about heavy subjects, which are very present in this collection. What are some ways you practiced self-care while writing this book, if any?

I won’t lie, writing these poems often became emotionally overwhelming. I think those who are compelled to write witness poetry (and I think most of poetry nowadays is witness poetry) are to some degree traumatized by what they have seen or experienced and share in their work. While the act of writing about trauma can be healing, the actual process asks you to relive it. Carolyn Forché calls the act of witnessing an atrocity an “impress of extremity”. I think it was Muriel Rukeyser who said that even the act of witnessing by reading witness poetry, the reader takes on some of the trauma of what they have read, I think that holds true for witness poets who give account or testimony on the crimes against others. I would sometimes need to take breaks and I had to learn to allow myself to switch gears; I wouldn’t stop writing but switched subject matter. Getting exercise, quality sleep when I could and allowing myself small pleasures like sunshine, a glass of wine or a piece of chocolate went a long way!

Where do your poems most often come from—an image, a sound, a phrase, an idea? Do you usually know exactly what path a poem will follow before you write it, or do you let the poem lead you, so to speak?

Every poet knows that when the muse will strike when she strikes, and you must accept the invitation and channel her or else the opportunity passes. I’ve found myself suddenly sitting down in stairwells and pulling out a notebook or my phone, furiously jotting down what comes. I think poets are Makars, as the ancient Greeks called us. We are in touch with something larger than ourselves that calls us to service. The greatest joy is in the process of writing in service to this calling. The poem always leads the way, giving rise to its form and imagery.

What are three books (poetry or otherwise) that you think everyone (or most people, at least) should read at some point?

Right now, I’m reading Arthur Sze’s Sight Lines, his craft is *incredible*- every poet should read him! Everyone, poets or otherwise, needs to read Citizen, by Claudia Rankine: the way she traces the impact of systemic racism and the damaging psychic trauma it inflicts is so important right now in the world. Also, Carolyn Forché’s In the Lateness of the World, she’s one of the great ones and this is her best work yet. Finally, if I can add a fourth book, it’s Siddhartha by Herman Hesse. It’s a work of fiction and such a classic story of a man who gets caught by the material trappings of the world and wakes up from it as an older person, I think everyone can relate to or benefit from this timeless tale of personal growth and awakening.

Sample poem from Raghead:

Raghead

Kuwait, 1988

It was more than penis envy, more than ancestral calling

of desert warriors, who understood

the power those filmy layers had to survive the sun’s

overwhelming

but oh man, the tactile allure of phyllo fabric between fingers

still thrills me.

Castration complex, straight-up sexual attraction—

no matter, but I used to don

my father’s headgear, preen in his bedroom mirror

(mmm, how handsome!),

my pulse pounding in Bedouin drumbeat fashion,

afraid to wrinkle it starched goodness

or be found in its gauzy tabernacle, admiring

how white material

flanked my profile like holy side burns, stiff wings

halo-like, delicate when left

hanging. I was outrageous in my faux drag,

feeling like a deck hand

struggling to master the art of a sail-flip

over a shoulder.

Just a curious teenager, bored over summer break, desirous

of my first dishdasha experience,

a lip-synching Boy George: karma karma karma chameleon!

Or pretending I was a nun

in habit, wagging a finger at my reflection in bouts

of mid-summer night’s imagining—

get thee to a nunnery!

No matter my precaution, my father finally caught a show

of my shenanigans, zeal of his pleasure

at my make-believe surreal as he taught me to fold

the cloth, tease its front

into a dent, under an anchoring rope of gahfiyya.

He dressed me up in a dishdasha

and we went for a ride. He let me drive the whole stretch

of Gulf Road, agreeing my name

for the night was Ibrahim el-Majnoon…

… and crazy we were, with my eyeliner’d uni-brow,

penciled moustache,

and him, still loud and lively, pretending I was the son

he didn’t have.

Oh ghutra: to me, you are everything but a rag.

Eman is a bicultural poet from Massachusetts and Kuwait. Her first collection, Raghead, was selected as the Editor’s pick in the 2018 New Issues Poetry Prize and was also the recipient of a Folsom Award. She earned an MFA in poetry from Arizona State University, a PhD in poetry from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and has worked as International Poetry Editor at Hayden’s Ferry Review and as Associate Editor at Prairie Schooner, respectively. Her poems and poetry translations have appeared in Blackbird, Borderlands, Mizna, Painted Bride Quarterly, and Aldus Journal of Translation, among others. She lives and keeps it weird in Portland, OR.