When did you first encounter poetry? How did you discover that you wanted to write poems?

My earliest encounters with poetry were through the Bible. As a young person raised Catholic the poems and songs of that ritualistic life were my first major exposure to poetry. Little poetry resonated with me in formal schooling. It wasn’t until I started listening to Bob Dylan in high school that poetry really penetrated. Dylan took me to Eliot, Pound, Blake, Whitman, and Ginsberg. Then I was off (my rocker!).

I wrote poems to my parents during high school, attempts at pure letters in verse, in order to convey the pains that just about any high school kid goes through with parents and the world at that time in their lives. I remember feeling very moved by the clarity of seeing, hearing, and feeling.

It took a few years before I had the urge and then finally the necessity to write poetry, however. At Northeastern University I met the poet Joseph DeRoche. I was studying economics, political science, and biology and didn’t have much room for classes in poetry or anything else. After a tip from a friend about DeRoche, I found myself visiting him in his office all the time. He had been in Robert Lowell’s workshop at BU and went to the Iowa Writer’s Workshop in the early 1960s when it was still novel.

I also started hanging out around the Grolier, around Stone Soup, and the world of Bill Corbett too. John Wieners lived here and loomed over that space. I thus got parallel exposure to the avant-garde pulse of poetry and world poetry. Between DeRoche and the ‘scene’ in those days, I told myself the best syllabus was the catalog of New Directions. I would read, try and imitate them, and bring the work to DeRoche’s office every week. These were some terrible poems for sure, but he would always start with the art and impulse and encourage and go from there.

With that impulse and his encouragement, I started calling myself a poet in the 1980s and have been at it ever since. Incidentally, Boston-area poet Martha Collins and I edited a posthumous collection of DeRoche’s poetry that was released in 2019 titled Ceremonial Entries published by Cervena Barva Press.

Do you have a writing routine? A favorite time or place to write?

At first, I didn’t have a routine and it would all just come. As my life has become more full I have had to make sure I make the time. After everything around the household is settled I work each night from 9 pm or so until who knows when. I will usually have the Celtics on with the sound off in the background. If it looks close in the fourth quarter the book gets shut and the volume goes up!

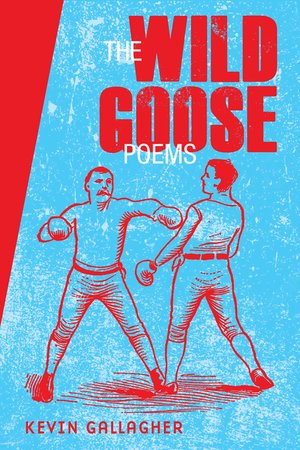

Over the past few years, I have been privileged to have some residencies that have given me the full-time space to write. In 2018 and 2019 I was a poet-in-residence at the Heinrich Boll Cottage on Achill Island, Ireland. Indeed, that is where the poems from my new book, The Wild Goose, were conceived. I’m currently a resident at the T.S. Eliot house in Gloucester, MA. These concentrated spaces are essential for me at this point in my life. I’m thankful to have received them and to my family for letting me sneak away to immerse.

Where do your poems most often “come from”—an image, a sound, a phrase, an idea?

Earlier I’d say most of my poetry was ‘lightning bolt’ poetry. An image, a sound, a phrase would come and I’d drop to the ground and let a draft electrify. As my life became more full I’d have to dodge many of those lightning bolts to get to work, drive the kids to practice, or any other thing that fills life.

For the past decade then my poetry has been a series of projects that are inspired by a bolt but then planned in their fullest sense. My 2016 book, LOOM, was inspired by the Freddie Gray murder. Rather than a one-time immediate reaction to those events, I went on an archival journey through history, ultimately constructing a book of poems that had a path. So when I have that time I can jump right in where I left off toward the broader plan delving deeper into the first inspiration, rather than sit and wait for another inspiration.

Which writers (living or dead) have influenced you the most?

Well, we named the family German Shephard “Rexroth” after Kenneth Rexroth so I guess I have to start there! His poems and translations are something I go back to again and again. So much there, he was among our best love poets, and of course the great poet of ecology. His translations from Chinese and Japanese are educational and an experience. Rexroth believed that a translation had to be a real poem in the language it is translated in—or it really wasn’t a poetry translation. Many scholars have had trouble with those translations, but they didn’t subscribe to his view that translating poetry is different than translating words. I go back to Rexroth again and again.

Muriel Rukeyser and William Carlos Williams are also poets that have influenced me the most that I keep going back to. Rukeyser’s “US. 1,” “Paterson,” and “In the American Grain” are among the models for the so-called ‘docupoetics’ that some of my recent books have engaged from. In addition to those two, Charles Reznikoff and Charles Olson have been big influences. I lived in Gloucester for some time and was able to read and breathe Maximus. Denise Levertov. Kenneth Patchen.

For a few decades, both Seamus Heaney and Derek Walcott lived in the Boston area for at least half the year. They would always launch their new books here and so their poetry and plays have also been very important to me. The greatest poetry reading I ever went to was at a packed house at St. John of the Divine in Manhattan—Seamus Heaney, Derek Walcott, Octavio Paz, and Joseph Brodsky. Those poets, Paz to me the greatest among them, have a scope and breadth that I haven’t been able to find in U.S. poetry. Because of this and because of the New Directions list I have been more influenced by international poets such as Neruda, Paz, Alberti, Picabia, and Jacob.

For the past decade or so I have been immersed in poets’ theater. In spoKe, the annual of poetry and poetics that I edit we did a special section on Bunny Lang. Frank O’Hara, Richard Wilbur, Amiri Baraka, Ed Bullins, and Eugene O’Neill are all important to me. Brien Friel, for me, is a writer for who I’d skip a party, movie, or even a basketball game for any time.

I can’t say I read much contemporary poetry. I go to the readings and openings of my friends and fellow poets here in the Boston area. Fanny Howe of course. I am serializing Amanda Cook’s letters to Maximus, and don’t miss new work from Jim Dunn, Danielle Legros Georges, David Blair, Ben Mazer, Marc Vincenz, and others. John Mulrooney is a great poet living in an area that needs more ink.

What excites you most about your new collection?

Sharing the ‘discoveries’ I made in writing the book. As I noted earlier the volume was conceived when in Ireland as a poet-in-residence at the Boll cottage. After Boll won the Nobel Prize he got a little suffocated in Germany and escaped off to Achill for the peace to write.

I am a quarter Irish, from the Great Famine. I hadn’t explored that part of me and set to do so in the book. The Wild Goose was the name of a literary pamphlet that the poet John Boyle O’Reilly and other prisoners made aboard the ship that took them to Australia for live imprisonment. In many ways, this book is my little post-colonial magazine about my Irish exploration. The first part of the book engages with Irish myth, colonization, and history. The second part is a series of poetic monologues based on the life of O’Reilly—who I had never heard of. There are five statues of poets in Boston—Phillis Wheatley, Edgar Allan Poe, Robert Burns (?!), and TWO of John Boyle O’Reilly.

O’Reilly was John F. Kennedy’s favorite poet. Born in Drogheda he became a Fenian who decided that infiltrating the English army would be the only way to topple English colonialism. He failed, was put in the harshest English jails, and almost escaped from each one. He was thus shipped to Australia but escaped to eventually come to Boston where he became the editor of the Boston Pilot, a noted poet, and abolitionist.

The third part of the book engages with my life in the area through the last name Gallagher as well as memories of my late father. The final section evokes the Aeneid as I search the underworld to talk to my father one last time and read him a poem I wrote for him.

Those Summer Saturdays

Saturdays too my dad woke up early.

Put on his grass-stained Sperry Topsiders,

his Kelly-green Bermudas with whales and paint,

then took the entire day to mow the lawn.

He’d snap open and fire up his Zippo

then mow two perfect rows with a Salem

Menthol 100 shrinking from his mouth.

Time to take a break for a Miller Lite,

to turn up Ken Coleman for the Sox score

to shout it out for everyone to know.

He’d save the empty cans to be redeemed

then light another butt for two more rows.

One lawn, three packs, and a case in a day.

And what did I know? What did I know?

Kevin Gallagher is a poet, publisher, and political economist living in Greater Boston, USA, with his wife Kelly, kids Theo and Estelle, and Rexroth the family dog. His recent books are Loom, Radio Plays, and And Yet it Moves. He currently edits spoKe, a Boston-based annual of poetry and poetics, and works as a professor of global development policy at Boston University.