When did you first encounter poetry? How did you discover that you wanted to write poems?

I didn’t really know I was interested in poetry and in literature until partway through my time at Wellesley College. When I arrived, I truly didn’t have a sense that I had any passions or interests at all. In my first year and my sophomore fall, I took a broad smattering of courses, including (with wild, and probably inappropriate, disregard for prerequisites in both cases) an advanced Shakespeare literary studies course and an advanced poetry creative writing course. I shouldn’t have ignored the prerequisites: I was very much not good enough for both of those courses! But I fell in love at first confusion, and I’ll forever be grateful to those professors for not chucking me out. Even when I was flailing around in both courses and even when I knew that I wasn’t making anything that worked, I loved wading through the muck. I loved what literature and poetry made me think of, the questions they made me ask, the uncertainties they animated.

Do you have a writing routine? A favorite time or place to write?

I am routineless. I envy writers who have specific rituals of composition! I am often working on multiple things at once across many mediums (a notebook, a Notes app, a word processor, email drafts, loose-leaf scribbles) and I essentially just jot things down whenever I have a moment and whenever an idea comes to mind. I do love the little desk setup I am now really lucky to have for the first time in my life! But I’m something of a chaos Muppet, as I’m equally content to have jotted down a few things on the back of a receipt as I am to sit there and reflect. (I do very much miss being a chaos Muppet at bars and at cafés, though.)

Where do your poems most often “come from”—an image, a sound, a phrase, an idea, or elsewhere?

This is equally as varied for me as the places that I like to write. All four of those have sparked something at various times, as has an overall sense of a shape (the visual of what I want the poem to make at the end, or a little outline of the shape of a stanza), a rhythm, a feeling, a story.

Which writers (living or dead) have most influenced you?

If it’s alright with you, I’d love to zig where this question zags! I’m really a magpie; so much of what I’ve read has stuck with me and has formed me, and answering this question sometimes feels like asking me which of my blood cells means the most to me. So instead of trying to provide a comprehensive answer to that question, I’d like to share with you the two collections I reread every year, which are Brigit Pegeen Kelly’s Song and Lucille Clifton’s The Book of Light.

What excites you most about your new collection?

The most fundamental story I wanted to tell in Arrow was that of the experience of living in the aftermath of severe domestic violence, other entangled forms of assault, and grief (in my case, particularly for my sister, who died in 2014 at the age of 24). This idea of an “aftermath” is complicated by the fact that there is no “after” violence or grief, especially when one thinks about how those things reverberate through the entirety of a life, and even more so when one considers the varying scales on which devastation and mourning take place—not only for one singular person, but for entire communities, for other people, for other communities, for other species, for planets, for ecosystems, across history, and so on. But I did also want to take the idea of “after” seriously, because the main autobiographical story that this collection tells is of my experience becoming able to embrace love, and joy, and care, and kinship—even when all of those things were weaponized against me or foreclosed for most of my formative years. This tension forms the tightrope that is Arrow’s throughline, and all of the other obsessions and preoccupations in the collection are lassoed to it, collide with it, or orbit around it.

Sample poem from Arrow

O Spirit

It takes work for a woman to welcome a fist

With her body. Fists are larger than the spaces

They make for themselves in a chest, or the holes

Into which we welcome them with longing.

Asking whether I wish for one now because I knew

Them well as a child is like asking if a volcano

Expels lava because, when a small mountain

Cloistered within seawaters, its first experience

Of heat was unbidden. The question

Requires a certain old knowledge of safety to ask.

What does it mean that the first time you saw a cock

It was raised in menace from a boil of shared blood,

The question says. Tell me the origin story of pain,

And tell me what happens to pain as it ages,

And tell me how the ocean-bottom dirt you grew

From tastes. Volcanoes understand differences

In kinds and in chords. The origin story of pain

Is abjection, foisted. Not a single stream of lava

Is like one that has come before or will come since.

All my lips make treacherous lights float in midair.

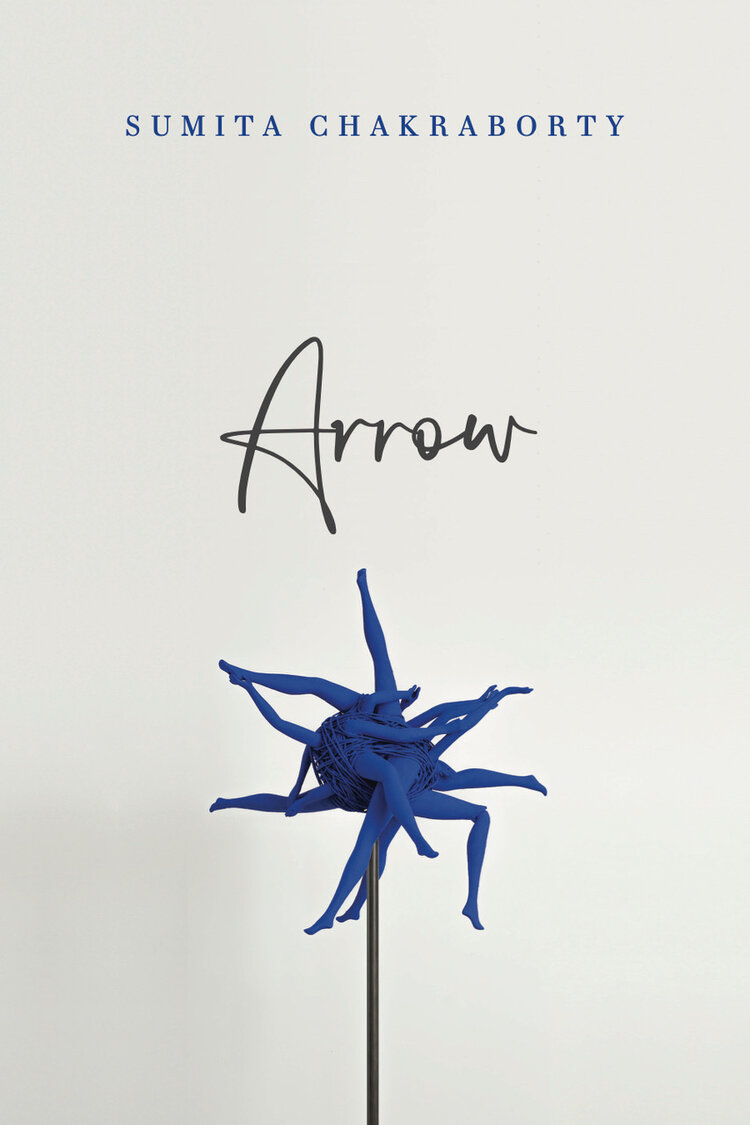

Purchase Arrow

Sumita Chakraborty is a poet, essayist, and scholar. She is Helen Zell Visiting Professor in Poetry at the University of Michigan – Ann Arbor, where she teaches in literary studies and creative writing. Her poetry has most recently appeared in POETRY , The American Poetry Review , Best American Poetry 2019 , Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly, The Rumpus , and elsewhere. Her scholarship appears or is forthcoming in Cultural Critique , Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and the Environment , Modernism/modernity , College Literature , and elsewhere. She is the recipient of fellowships and honors from the Poetry Foundation, the Forward Arts Foundation, and Kundiman. Her debut collection of poetry, Arrow , is out now from Alice James Books in the U.S. and Carcanet Press in the U.K., and has received coverage in the New York Times , NPR, and The Guardian . Find her on her website at www.sumitachakraborty.com or on Twitter at @notsumatra.