Tell us a little bit about your new collection: what’s the significance of the title? are there over-arching themes? what was the process of assembling it? was is a project book? etc.

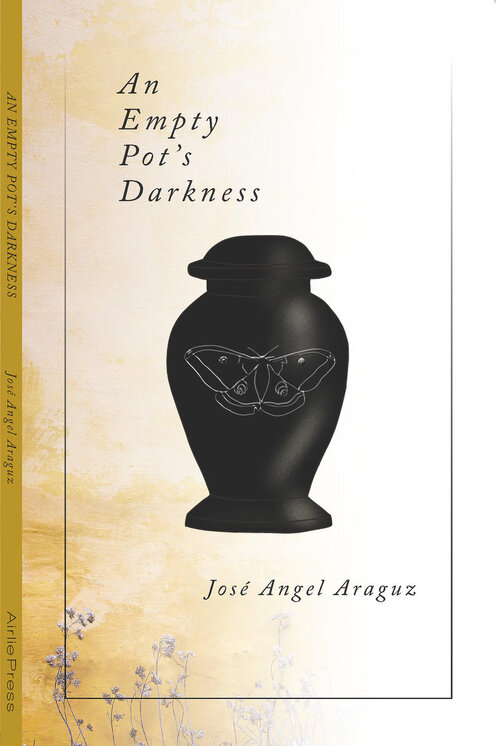

In terms of the title, I always like to find a word or phrase that seems significant. As this collection deals in elegiac sequences, I struggled a bit at first. The phrase “an empty pot’s darkness” is in one of the few poems not dealing directly with death. Soon as I singled it out and took it out of context, I saw the fruitful ambiguity it lived in. I see the pot working as both a cooking one (as in the poem it’s from) but also a funeral urn (one of the sequences does deal with a friend who was cremated). And pulling further out, I see more metanarrative meanings: that we are the mortal pots left empty when we die; also, since the poems in each sequence are strictly eight lines each (which I call octaves for the book’s purposes), form becomes a kind of pot whose darkness I revel and roam in.

Themes range from friendship and mortality, but also the writing life. I elegize two writing friends from my hometown, Corpus Christi, Texas, poets who had a major influence on my life early on. I’m also in conversation with dead writers. William Stafford gets a nod, so does William Blake in the naming of two sequences “Octaves of Youth” and “Octaves of Experience,” respectively. I also have a sequence of octaves in conversation with the work of Octavio Paz. Mortality is a theme not only in elegy but in a personal way as well. In the sequence “for La Llorona,” I interpolate some of the lore of the figure La Llorona as portrayed in folksongs to speak indirectly about a past problematic relationship. In the closing sequence “An Empty Pot’s Testament,” I delve into some of my own darker moments in my life. The tone I go for is one of public testament, similar to the way Pablo Neruda ends his poetic epic, Canto General. For me, it was important to acknowledge the gift that it is to get to live to write this book.

As for process, this collection is comprised of three sequences published in an earlier chapbook (Corpus Christi Octaves, Flutter Press) along with four newer sequences which take on the thematic and formal project of those early sequences and takes them in new directions. What mattered to me in pursuing these octaves as a collection was putting these themes and experiences in conversation with each other and honoring the richness of that conversation.

This is your fourth collection of poetry. How does this collection feel different from the others?

In a lot of ways, this may be my most vulnerable book. To flip through it, the individual poems are each eight lines and without titles. Which means that the poems hinge on the phrasing I work out in a short space. I remember after a reading in 2012, one person came up to me and asked: “Is that all you have? Short poems?” This comment came long before this collection, but it has stayed with me. My immediate reaction was to double down and write a hundred more short poems, followed by an anxiety-driven rush to write a hundred long poems. I share this story and reaction to show that I’ve always been sensitive to formal decisions. When this book came out, I came back to that conversation in 2012 and felt self-conscious again.

Vulnerability and form intersect in another way in this collection, namely in the formal and conceptual decisions made. Formally: along with each poem being eight lines long, each has an individual syllabic structure. Some sequences follow the same syllabic structure, and some vary widely, but each has been worked out to fit the individual lyric. This attention to form down to the syllable was important for me as it was a way to give personal material torque and resonance, a way to trouble the traditional elegy both in tone and approach. I didn’t want a high tone; I wanted voices present, my own and others, and I wanted images clear. Conceptually, there are all the personal and literary homages and references that the poems make. I didn’t want to hand readers a book riddled with footnotes, so I worked at each poem for a clarity that stood alone from whatever outside reference it could be making. Ultimately, it’s a book of poems and not an academic treatise. If you catch a reference, that adds to the experience, but it isn’t the point. I worked so that something of my friends and life could be caught across the troubled syllabic terrain.

I consider my previous book, Until We Are Level Again (Mongrel Empire Press), a love letter to the short lyric; this collection feels like a set of notes passed in secret to the octave form.

Which writers (living or dead) do you feel have influenced you the most? Are these influences evident in this collection? How so?

Sharon Olds is one of my biggest influences, I feel. Her steadfast attention to honoring the linguistic richness of each poem as well as the personal narrative that informs it is something I aspire to. I mention William Stafford in the book, but the poet who led me to Stafford, Naomi Shihab Nye, is also a great influence. Her poems kept me alive at a specific time in my life, one covered in this book actually, where I lived in a house without electricity. Without light, her poems kept me able to see the world. In terms of this collection, I have to mention the Greek poet Yannis Ritsos whose short poems teach me so much. He has a sequence for the poet Cavafy where he elegizes him, at times focusing on everyday objects, like the poet’s glasses. Ritsos’ sequence on Cavafy is definitely a direct influence on this book.

Tell us about your love for the short poem.

When I was in second grade, the teacher then taught me the 5-7-5 version of haiku. I remember writing about all the things that interested me then: Ghostbusters, aliens, vampires, ghosts, etc. That was perhaps my first experience with the short poem, one that I can only vaguely recall; what I do remember is just the joy of it. Over the years, I continue to admire the great possibilities in a variety of short poetic forms, how short forms work like bouillon cubes to hold so much in a small space. From haiku then later tanka, I later learned to engage with lyric aphorisms as evident in my chapbook The Book of Flight (Essay Press). The work of Olivia Dresher had a great effect on me in this regard. Octavio Paz himself said that the short poem is the hardest to write. I agree, and would add that it is also one of the most joyous to write.

What are you working on now that the book is out in the world?

I have a number of projects that I’m always working on, each ranging from complete to in-process. The most complete of these are a poetic memoir and two poetry collections, one dealing with religion, the other with politics. As I say that I realize such heavy topics aren’t easy to separate as easily as all that, ha.

What art, writing, or media is moving you right now?

I’ve been keeping Olivia Dresher’s latest book, A Silence of Words (Impassio Press), nearby these days. Rosa Alcalá’s MyOTHER TONGUE (Futurepoem, 2017) and her work in general continues to be illuminating and formative in a number of ways. I also keep coming back to Rainer Maria Rilke, might be the third time I return to his work across the twenty years I’ve been writing. Still something I’m learning from him.

As for art, the artist Karla Rosas (KARLINCHE) has been doing some dynamic work that engages with and subverts typical Mexican immigrant narratives. I was excited to feature her work in my first issue as Editor-in-chief of Salamander Magazine.

Also: I’m always listening to new music, and if you’re friends with me long enough, I might share what that is. As for TV, The Witcher on Netflix is impressive for its nonlinear approach to narrative as well as for its honoring and updating of fantasy tropes.

sample poem from An Empty Pot’s Darkness

You lived without power like a

grudge, lit lamps as others puzzled. This is just

how one lives. The nights I lived there, I stumbled

in the dark and wrote my poems by

the light of a kerosene lamp.

When the light gave out, I would write by the moon.

When the moon gave out, I’d write trusting the words

would still be there in the morning

Purchase An Empty Pot’s Darkness

José Angel Araguz is a CantoMundo fellow and the author of seven chapbooks as well as the collections Everything We Think We Hear, Small Fires, Until We Are Level Again, and, most recently, An Empty Pot’s Darkness. His poems, creative nonfiction, and reviews have appeared in Crab Creek Review, Prairie Schooner, New South, Poetry International, and The Bind. Born and raised in Corpus Christi, Texas, he runs the poetry blog The Friday Influence and composes erasure poems on the Instagram account @poetryamano. A faculty member in Pine Manor College’s Solstice Low-Residency MFA program, he also reads for the journal Right Hand Pointing and serves as a co-editor of Airlie Press. With an MFA from New York University and a PhD from the University of Cincinnati, José is an Assistant Professor of English at Suffolk University in Boston where he also serves as Editor-in-Chief of Salamander Magazine.