When did you first encounter poetry? How did you discover that you wanted to write poems?

Poetry seemed a little exclusive to me when I was younger, a little chi-chi. But that was only because I wasn’t exposed to very much of it. In college I was interested in trying my hand at fiction but couldn’t get into the workshops: there was a lottery for the beginner-level courses and a submissions process for higher-level workshops. So I focused on painting, and through that—long story short—ended up one summer in a barn on the west coast of Ireland, listening to C. D. Wright read her poems. She could make a believer out of anyone. One poem in particular, “More Blues and the Abstract Truth,” from String Light, had these remarkable combinations of plain speech and poetic dexterity, and the suggestion of a narrative paired with unaccountable lyric associations. It was strange and wonderful and inviting. When I returned to school, I discovered Frank O’Hara, Kamau Brathwaite, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, this whole new world of amazing thinkers and artists. Pretty much I never looked back.

Do you have a writing routine? A favorite time or place to write?

I don’t seem to be very good at routines. I wish I had one for writing, a healthy, first-thing-in-the-morning type of approach, but I don’t. Instead, I chip away all day, steal moments, squeeze in bursts. I am a serious night owl, however—like I really come to life around 11 p.m. Often I’ll start writing when the city’s grown quiet and rather than the din, only some sounds assert themselves: crickets in the park, arguing neighbors, an ambulance, or the dog in the apartment upstairs, keening in his knock-kneed doggy dream. If I could, I’d write from 12-4 a.m. every night, like my own private retreat. But as I think about this question more: these are the times I actually sit down to write. All day long, though, I’m turning lines and rhythms over in my mind. Recently I had an MRI and was (thankfully) distracted by an instinct to scan the various thumps and clangs—to catch their expressive meter. So, ultimately, my routine is probably just a kind of wild all-day immersion. Writing’s always on my mind.

I noticed that the poems in this book use a lot of natural imagery; is that something that has run throughout your work, or did it emerge as a theme specifically with this collection?

Natural imagery is a primary language for me, so definitely—it features throughout The Clearing, even in poems about love and loss and very human interactions. Maybe because I grew up in rural areas, I tend to experience the world in natural terms. When I come across something decidedly urban, like Frank Gehry’s “falling down” building at MIT, my mind is still skimming for trees and critters, for a foothold. In Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, Marco Polo says that no matter where he travels, he’s always, in a way, exploring Venice. His hometown is his default, the basis for any comparison—new places are like Venice or unlike Venice or some combination, but Venice always hovers there, like a permanent transparency. With poems, whenever I’m mulling over a problem, or trying to sort a paradox, I find myself considering how it works in the natural landscape I knew before I understood much else. The Clearing is rooted in place, mainly central Pennsylvania and southwestern Colorado. Both are environments that gain a good deal of identity from their terrain and from the layers of living they hold: everything from bears and avalanches to cornfields and calves’ navel cords. There’s beauty, and there’s cruelty. Images, if thoughtfully rendered, are always distillations, haiku-like. For me, natural images tend to suit best the stories I know, the people I know. They act as a record, a kind of material culture, one I’d like to do what I can to spotlight.

On a similar note, this collection makes quite a bit of use of fairy- and folktales. What made you want to tackle those stories?

Well, it’s funny. I think there are two outright references to fairy tales in the book: the title poem, which pushes back a bit against the tendency to romanticize violence toward women in traditional tales; and “Fable,” a poem about new ways of looking at the change of seasons. Other than those (and even with them), the poems are all based in personal experiences, family stories, or in the regional histories of places I’ve lived or spent time. There are bears and wolves and bats and swans, but these are actual bears and wolves and bats and swans, not gestures of fantasy. The bodies are real, their toils heavy. To quote Diane Seuss in “I Look Up from My Book and Out at the World through Reading Glasses,” “All trees are trees. / Death to modifiers.” On one hand, it gives me pause when rural narratives are classified as “folk tales.” On the other, I love how that designation honors mettle, collaboration, communal storytelling and oral histories, mystery, brutal paradox, and the otherworldly gospel of the ground. All of these things are important to me. They’re probably the reason I write.

Were there any influences you found yourself returning to while writing this book, e.g. musical artists, other poetry collections, movies, etc.?

In retrospect, I think some of the book’s inspiration might have come from a short, unstabilized video on YouTube called “Bear Fight Rockaway NJ August 14 2014,” posted by the account J. Domzalski. Something about the video, including its blurs and hiccups, seems essential. It breaks through the noise. The way cars casually pass by, the trash bins, the bears’ posturing and the surprising intimacy as they struggle—not to mention the thin, thin line between us and them: The scene captured is profoundly real, raw and urgent, but the metaphors introduced are also powerful. In The Clearing, the video’s influence is not so much topical or thematic, but it definitely emerges in things like perspective and critical distance. In terms of other poets, I read a lot. Like so much that I think my town librarians might roll their eyes a bit when they see me coming. And I wouldn’t blame them! But it’s how I water my garden. So The Clearing is indebted to many great writers. Some, like Carl Phillips, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, and William Stafford, were the sources of epigraphs or specific phrases. Others—B. H. Fairchild, C. D. Wright, Marcus Wicker, Mary Jo Bang, James Galvin—have a raw, unrushed spirit of inquiry, and a commitment to careful observation, which I greatly admire, and which I’m always attempting in my own work.

What are three books (poetry or otherwise) you think everyone (or at least most people) should read at some point?

Oh, three is hard! But here goes: Four Reincarnations by Max Ritvo. Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith. Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers by Jake Skeets. And if I could just *squeeze* in a little bit of prose, a wee coda: The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy, The Reawakening by Primo Levi, and In an Antique Land by Amitav Ghosh.

Sample poem from The Clearing:

Week Six of the Fire

After Aimee Nezhukumatathil

I have faith in the spindle of an aspen.

I have faith in its sugar-drenched bark, in the scorched-butterfly

bruise left by an elk’s incisors. I have faith in the tree’s skeleton

branch, in the flat stems helping each leaf survive the whiplash of mountain wind, I have

faith in anything with a steady tremble. In light that leaks through.

I, too, once trusted the itch of a velvet antler

to carry my hunger toward a grove. I trusted

something–instinct, desire, the buck’s lung-shaped tracks–to keep me moving

through the fire, through scarves of molten citrine wafting in a vaulted sky, which is to say

out from under your body, beyond the memory of its long, easy weight,

its stack of ashen bones.

The fire blooms into its sixth week.

My faith grows heavy, a cloud baggy with grim rain.

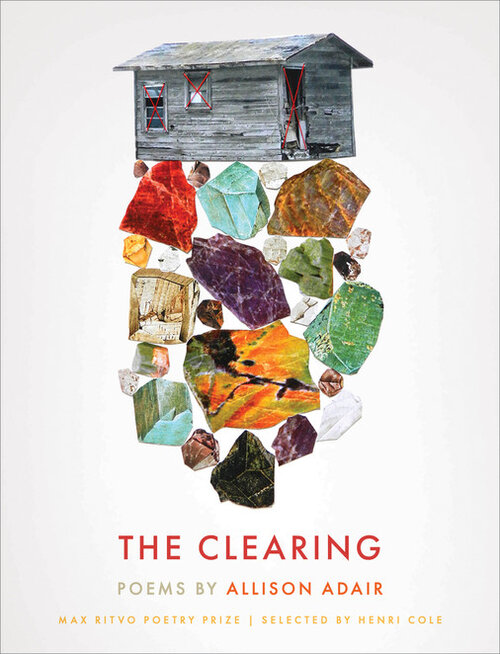

Allison Adair’s debut collection, The Clearing, was selected by Henri Cole for Milkweed’s Max Ritvo Poetry Prize and was named a New York Times “New and Noteworthy” book. Allison’s poems have appeared in American Poetry Review, Arts & Letters, Best American Poetry, Kenyon Review, Waxwing, and ZYZZYVA; and have been honored with the Pushcart Prize, the Florida Review Editors’ Award, and the Orlando Prize. Originally from central Pennsylvania, Allison teaches at Boston College and Grub Street.