When did you first encounter poetry? How did you discover that you wanted to write poems?

My mother read poems to me, When We Were Very Young, “James James/ Morrison Morrison/ Weatherby George Dupree/ Took great/ Care of his mother/ Though he was only three” and I was moved to write a poem now and then as I grew. But I needed to write after my friend, Caroline, died, a difficult, protracted end. She’d asked her friends to promise to wash and shroud her. After her death, I had to do something with the images that were haunting me, and so I wrote, thinking then that Caroline’s death was my only subject.

Do you have a writing routine? A favorite time or place to write?

I don’t have a routine, just write when a germ of a poem starts rattling in my head. I’m blessed to be living by the water in our vacation cottage where our kids banished us to be safe when the pandemic began. Poems often begin in this place.

Where do your poems most often “come from”—an image, a sound, a phrase, an idea?

My free-writing notebooks from weekly sessions with other poets — we trade prompts and read to each other — are full of ideas that may grow into poems. Or I may start from something I observe in nature and the poem will tell me what it is saying about my life. The beginning might be anything — a conversation, a film, something I’ve overheard.

Which writers (living or dead) have influenced you the most?

I’m always carrying a poet, living or dead, around with me, wanting to absorb osmotically, what they do, and how. I probably began with Auden, until he seemed to me to be a little churlish. Then it was probably T. S. Eliot, Charles Wright for a long time, especially A Short History of the Shadow. I feel like Wright’s been walking ever so slowly toward his own death and searching for meaning. Frank X. Gaspar’s Late Rapturous, the gorgeous way he expresses that rapture. Thomas and Beulah by Rita Dove, her grandparents’ struggle through their lives, so beautiful, so succinct. Jane Hirshfield wrote one of my all-time favorite poems, If the Rise of the Fish. Bob Hicok, whose way of connecting seemingly disparate events, strung through with politics and humor, I so admire. I even wrote him a fan letter when I read his essay that seemed despairing. He was feeling that his work didn’t matter, that poetry didn’t matter.

What excites you most about your new collection?

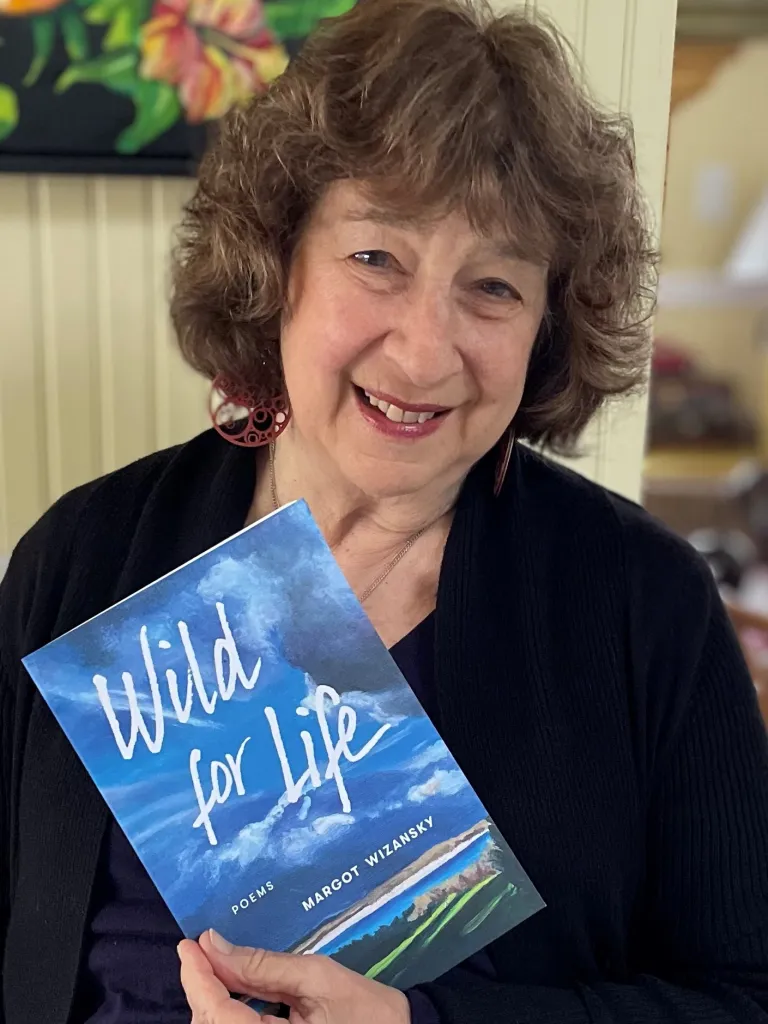

My chapbook, Wild for Life, was written after I had a near-death experience, a burst aorta and a coma that most people don’t recover from. “Wild for Life,” the title poem, was the first poem I wrote when I was healing, wrote it when I thought I’d never be able to write again. It’s a memoir in poems of that first year. Once I got started, the poems came in a rush. I had readers and my publisher/editor, Eileen Cleary, Lily Poetry Review Books who helped me with fine-tuning. Eileen generously had my daughter do the book design, and let me use my own painting of a wild sky for the cover. The whole experience was healing for my family and me. Readers with serious illness have told me the poems resonate with them, and medical professionals say the book can be a resource for students who are learning the art of healing.

I MUST HAVE BEEN WILD FOR LIFE

I held fast to the tiniest bit,

held on down to my very beginning.

Because I felt no agonies, why was I not

joyful, why so quiet and so slow? Joy seizes

the rising moon. Why wasn’t I holding

the other end? There’s a black line on my chest,

lumpy and scarred. The week of my coma,

what was it, absence or sleep? Memory

does not assail me. It was only my heart

beating. Was I in my body, deep inside,

or had I left? I can’t let it in all at once,

just a small portion of blue sky and a yellow

flower whose name I don’t know.

Half the garden died while I was recovering

and the other half greets me stiff-armed.

I sit upright and watch the kind of TV

that simply runs my mind. Was I supposed

to have died? Did I? Was I brought back?

I could have slipped over so easily,

the thin margin visible to me now.

Margot Wizansky’s poems have appeared on line and in many journals such as The American Journal of Poetry, Missouri Review, Bellevue Literary Review, Ruminate, River Styx, Cimarron, and elsewhere. She edited two anthologies: Mercy of Tides: Poems for a Beach House, and Rough Places Plain: Poems of the Mountains. She won two residencies, one with Writers@Work in Salt Lake City and also with Carlow University in Sligo, Ireland. Margot is retired from a career developing housing for adults with disabilities. She lives in Massachusetts. Wild for Life is her first published chapbook.