When did you first encounter poetry? How did you discover that you wanted to write poems?

I found poetry everywhere in the remote mountains of southern West Virginia where I spent the first

part of my childhood. I remember teaching myself how to write a 4 in the dirt with a stick, and noticing

that it looked like a treehouse. Even before I learned letters, I knew that words had power. I loved

pretending that I was writing a story with swirls and squiggles. I also enjoyed swinging fallen branches

around in the air, all those loops in my body making a dance.

In 1969 I was 13, living in New Bedford, MA, writing poems, and questioning everything. Two books I found that included poetry, Black Fire and Sisterhood is Powerful, were instrumental in helping me to understand what was going on at that time in the civil rights and women’s liberation movements. As a college student, in the context of feminist social justice activism, I studied poetry and movement arts and began to compose pieces that combined spoken word, gesture, and dance. I have since given these weavings the name Poemotion.©

Do you have a writing routine? A favorite time or place to write?

Material for a poem can arrive at any time of day or night. When I’m paying attention, I notice the spark and how it feels in my whole body. To take the next step of entering the unknown through that portal of light, I like to write first thing in the morning with pen and paper. After some handmade drafts, I take it to the computer to revise and print. I jot notes whenever and wherever. When I’m out walking and have nothing else to write with, I use a sharp rock on deadwood or inscribe the ground. The physicality reminds me that words begin through motion – breathing, blood and bone pulse, shape of tongue, textures of ground and sky.

Where do your poems most often “come from”— an image, a sound, a phrase, an idea?

My poems come from a personal and collective place of appreciation, celebration, and a deep desire to express the wonder of being alive. In reading, writing, listening to, and performing poetry, I become more aware of how my singular voice is woven of myriad voices – past, present, and future. As I explore and generate connections within my sphere of awareness, I expand my ability to notice and learn from voices beyond my direct experience. This practice supports and promotes healing transformation.

Which writers (living or dead) have influenced you the most?

I am extremely grateful for the countless poets and artists of all kinds who continue to influence my work, beginning with my parents and siblings. When I was a young woman coming out as a lesbian, Audre Lorde’s bold presence and poems were an invaluable source of inspiration regarding embodied poetic activism. She assured me then, and her spirit continues to inform me, that not only can I do this work, I must. Contemporary writers and ancestors who have influenced me, too many to name here, include poets from around the world through thousands of years. The first known recorded author, Enheduanna, a Sumerian woman who lived circa 2300 B.C.E., continues to remind me that poetry is a vast conversation, and that all of our voices echo and weave.

What excites you most about your new collection? (Significance of the title? Overarching themes? Process/experience of assembling it?)

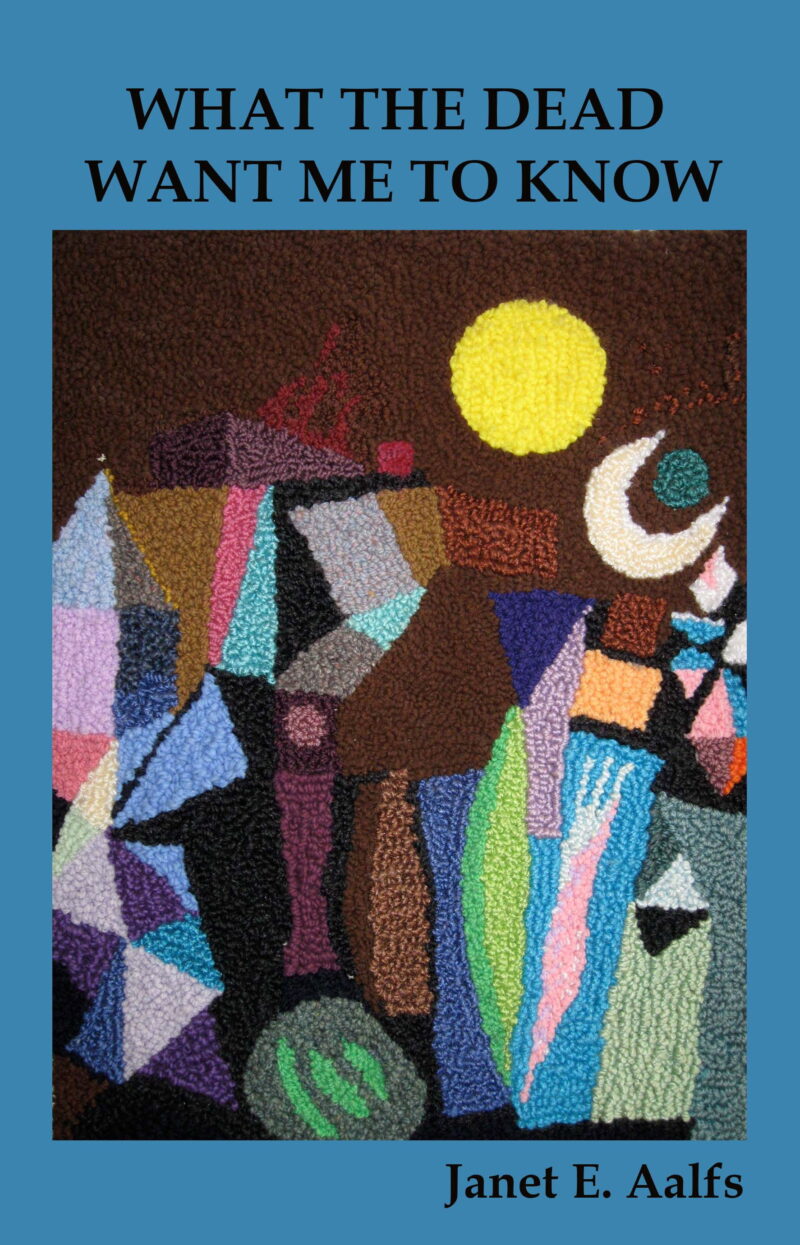

The process of creating and sharing What the Dead Want Me to Know continues to be a spirit journey

of learning how to listen more closely and intentionally on all levels. Balancing harmonious and

dissonant elements, and being able to hold paradox without splitting, is what the “artivist” path keeps

growing in me. This book begins with a poem located in 4th century and current Suzhou that honors

two Chinese women, one the creator of a spiral poem embroidered in silk, the other a dear Taiji teacher

and friend. The second section is a long love poem for the West Virginia communal ground where

poetry and social justice activism took root in my life.

Many beloved people, some alive and some who have passed, appear in these pages to help take

collective conversations further into the world. I’m grateful that the publisher was excited to use one of

my mother’s hooked yarn tapestries in designing the cover. Serendipitously, this book went live in 2022

on her 99th birthday anniversary the year after she died. A poem question on the third section’s title

page keeps encouraging me in the process of moving through loss and grief: “Shadows in the fabric of

birdsong. / Silence light as bones. / We follow wings / through the river asking / why have we feared

death / as if it is not / also what sings?”

Janet E. Aalfs is the author of 3 full-length books of poems and several small press and self-published chapbooks. Her writing is widely published in journals, anthologies, and online, most recently in Soundings East (Pushcart Prize nomination), How to Write a Form Poem, Words to Live By, Compass Roads, and Emulate. Former poet laureate of Northampton, MA (2003-2005), 8th degree black belt, master Tai Chi instructor, and founder/director of Lotus Peace Arts at Heron’s Bridge, Janet is the recipient of a Leadership and Advocacy in the Arts Award from the University of Massachusetts. She received an MFA in poetry from Sarah Lawrence College, and has been a featured presenter at many events and conferences including the Dodge Poetry Festival; the Mass Poetry Festival; Split This Rock; Power of Words Transformative Language Association; the Hudson Valley Writers Center, and performing arts teaching exchanges in Cape Town, South Africa. Janet has been offering interdisciplinary arts education rooted in feminist social justice activism locally, nationally, and internationally since 1977. www.heronsbridge.org