When did you first encounter poetry? How did you discover that you wanted to write poems?

I compare my poetry encounters in middle and high school with being forced to swallow regular tablespoons of cod liver oil. I was told it was good for my literary health; all I knew is that my brain didn’t like the taste. In college, T.S. Eliot utterly changed my taste. I was so happily drawn in and disoriented by “The Waste Land” and “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” They were knotholes into meaning, emotion, history, religion, social commentary, psychology. They contained multitudes far beyond the mere and minimal number of words on the page.

When I arrived at Oxford University for graduate school, I was finally ready to study and write poetry. I discovered that the form’s natural shortness, its heavy reliance on single words and their arrangement, and the power of compression suited how I see my world. There’s certainly a correlation between this and my love of espresso, neat whisky, and unobstructed views of vast landscapes and seascapes. It gets you there more quickly.

Do you have a writing routine? A favorite time or place to write?

I wrote both Small Gods of Summer and Hope Is A Small Barn in the very early hours of the morning, typically on weekends, for three reasons. During this span of years, my three daughters were young, awoke early, and turned into two-legged distraction machines as soon as their feet hit the floor. I had to out-wake them. Also, because management consulting is my vocation, I often spent weekdays on the road and had no mindpsace for creative writing. Finally, the hours around sunrise are so placid and open, which makes the passage of poems in and out much easier for me. Faster, too, with caffeine.

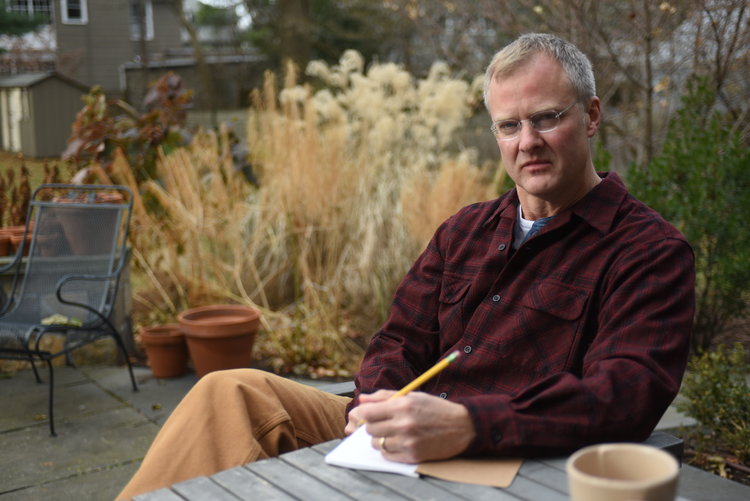

I tend to write in two locations. On the third floor of our Victorian house in Jamaica Plain is a garret that has just the right amount of light, comfort, and remoteness for concentrated periods of writing. Our home on Cape Cod is an 1830s farmhouse with a deck that looks out on two meadows, an ancient stone wall, and woods running down to the bay. That view, with all of its space, gives me so much room to write.

Which writers (living or dead) do you feel have influenced you the most?

Philip Larkin, Elizabeth Bishop, T.S. Eliot, Robert Lowell, Robert Frost, Rilke, Wallace Stevens, and Sylvia Plath. Seamus Heaney influenced me while I studied under him at Oxford, but not with his poetry. While I greatly admire his work, the kindness and generosity he showed me and other aspiring poets is what stays with me.

Where do your poems most often come from—an image, a sound, a phrase, an idea?

The majority of my poems start from something small and concrete, i.e. bound by time, space, size. This includes phrases, vignettes, specific locations. Things I can see the rough beginnings and ends of. Shards of something bigger, although I often discover what that something is in the process of writing.

These beginnings are often yolked with a particular feeling I have. I don’t believe I’ve started a poem from an idea or concept, or from an abstraction (like death, betrayal, compassion). In the act of writing creatively, I struggle to narrow something wide or shape something amorphous. Oddly, this is exactly what I do in my day job as a management consultant. I work to boil data and information down into insights.

The locus of many poems in Small Gods of Summer is imagery, often of place. In Hope Is A Small Barn, I tried to infuse many of the poems with music – alliteration, rhyme, rhythm, meter – without drawing too much attention to them.

Tell us a little bit about your new collection. What’s the significance of the title? Are there over-arching themes? What was the process of assembling it? Was it a project book?

Since I was a boy, I’ve been fascinated by barns, equally by their pure functionality and their architectural beauty. When I was growing up, my aunt and uncle lived on a 100-acre farm that had been in our family for 200 years. I was always drawn to play in the cavernous dairy barn. It was recently torn down. I also had to remove an ancient barn on our Cape Cod property because it had aged beyond repair. I feel sadness and regret about demise of these buildings. So, the title has twofold significance. The hope is personal: I would like to build my own barn. And it is such a powerful symbol unto itself. On the surface, the title poem is about building a barn: it’s in the form of a triolet, so it has an architecture, a symmetry.

I’m fascinated by and respectful of poetry as a form, so, in addition to the triolet, I’ve included a sonnet, villanelle, shape poem, blank verse, and a range of rhyme schemes. The majority, though, is in free verse.

The themes I explore in this collection are bottomless for me. I also mined them in Small Gods of Summer: childhood and fatherhood; the facts and acts of memory; the realities of aging; the bonds and binds of relationships; the significance of place; death, of course. However, I did not write any of the poems in Hope Is A Small Barn with their ultimate grouping or sequencing in mind. The Antrim House publisher and my editor, Wyn Cooper, suggested the four-chapter layout based largely on patterns of themes and subjects they observed.

Many of the poems in Chapter I are about the sensory experiences of immersion in external landscapes. And how those experiences help map one’s internal landscape and shape deep personal meaning. Bays, oceans, lakes, fields, islands, and seasons – summer, especially – feature throughout. Chapter III’s poems map internal landscapes carved by human relationships: family, friends, marriage. Some describe how death observed and felt changes everything, causes revisions, affects decisions. I originally conceived “The Magic Lantern” and “The Hunt” as single, chapbook-length works because they are long narrative poems that follow an arc. However, the publisher and my editor, Wyn Cooper, persuaded me to include them as Chapters II and IV because they combine virtually all of the themes examined in the Chapters I and III.

“Rescuing Mermaids” – A sample poem from Hope Is A Small Barn

When an envy of mermaids

beached itself,

my daughters set about “

rescuing them

from certain death

or something worse.

I suspect that they administered

a kind of serum

passed from hands to scales

in palmed cups of seawater.

No man can comprehend this,

of course.

Nor could I decode

what they spoke to the revived,

but figured it must have been

gentle dissuasion.

One by one, the flopping subsided

and they let themselves

be dragged seaward

by the hands,

their limp tails leaving trails

in the sand

and slicks of oil

flecked with glitter.

They sank at the surf line

with what must have been resignation.

I imagine that they recovered

under the breaking waves

and darted through kelp curtains

into the familiar.

Later, my girls reported

that they heard keening

while they were diving for shells.

They explained

that it was less a protest

than a peal of regret.

Gregory LeStage lives in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts with Julia, his wife of twenty-five years, and his three daughters, Chloë, Sadie and Elsa. He is a former academic who left university life for the challenges of the business world and is currently an executive at a global management consulting firm. His passions include an old farmhouse on Cape Cod, his workshop and tools, a 1940 Farmall tractor, and a 1949 Chevrolet pickup truck.

He earned his PhD and Master’s from Oxford University, where he also taught, and his BA from Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut. He earned his high school diploma from The Hill School in Pottstown, Pennsylvania.

His first collection, Small Gods of Summer, was a 2014 finalist for the Eric Hoffer prize. Hope Is A Small Barn, published in 2017, was a finalist for the Julia Ward Howe prize. His poems have appeared in a number of publications; and his articles, interviews and reviews have been published by Poetry Review, The Times Literary Supplement, Times Higher Education Supplement, New Writing, Notes & Queries, and Oxford Today.