Small Press Interview Series: aforementioned productions

a conversation between Erica Charis-Molling and co-founder Randolph Pfaff

Erica Charis-Molling: Let’s start at the beginning. How did the press get started?

Randolph Pfaff: First of all, thanks for including us in the interview series. We’re longtime Mass Poetry fans and the festival is a highlight for us each spring.

In 2005, both Carissa Halston (our Editor-in-Chief) and I were in our early twenties and living in Cambridge. We had talked for a while about starting a literary magazine and had also been working toward staging a group of short plays that Carissa had written. As we were rehearsing the plays, setting up ticket sales, etc., we realized that we needed a “company” name, which is how we landed on Aforementioned Productions. We’ve produced theatre off and on since then, but we’re primarily focused on publishing apt, our literary magazine, along with chapbooks and full-length collections, as well as hosting readings and other live events.

When we started out, we had very few resources. I’m sure most people reading this interview will understand the difficulty of starting any sort of literary venture without institutional backing. We initially wanted to publish issues of apt in print, but we were woefully underfunded. We decided to publish online, which was still a strange and wide-open space in 2005. It’s odd now to think about how much has changed in less than fifteen years. At the time, there were few social media platforms and most online communities were smaller and more difficult to find. We ended up publishing twenty-four issues of apt online and it was a challenge. The site was hand-coded, we read submissions via email, and we even hung up flyers in Harvard Book Store and other locations around town to get the word out. A lot has changed since then, but the learning experience of building so much of the press without a map has made us resilient.

ECM: Tell us a bit about the press. What sets your press apart from other publishers?

RP: I think the biggest thing that sets us apart is our commitment to our authors. We value quality over quantity and we put out a limited number of titles. We work collaboratively with our authors over many rounds of editing and revision to ensure that we’re all proud of the final product. In addition, we only work on book-length projects with authors whose work we’ve published in apt. This provides us with a pipeline of amazing writers who we know we can work with and who understand what we do and how we go about it.

ECM: Can you give us a preview of what’s forthcoming from your catalog, as well as what in your current catalog you’re particularly excited about?

RP: We’re very excited about the tenth print issue of apt, which is due out early next year. It’s focused entirely on climate change and we’ve already accepted several engaging, incisive pieces.

As for our current catalog, it’s difficult not to talk about every book we’ve published. To avoid this answer being egregiously long, I’ll focus on a book we always sell out of at the Mass Poetry Festival.

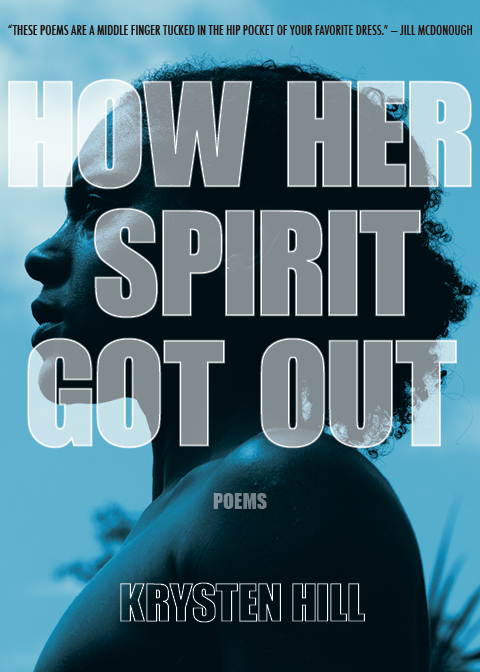

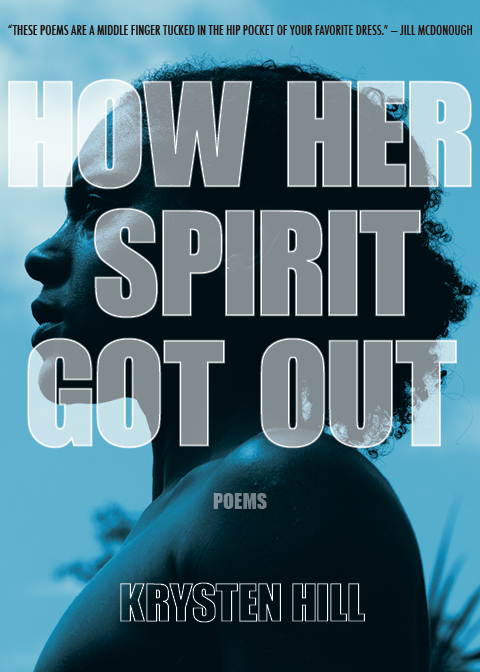

Krysten Hill’s How Her Spirit Got Out is an astounding debut collection that we published a couple of years ago. It’s a book we love, of course, but I’ll take a hint from Reading Rainbow and say, “don’t take my word for it.” Joyce Peseroff wrote a thoughtful review of the book and said that the poems have “a voice that is beautiful and raw, intimate yet public, both confident and vulnerable.” The dichotomy that Peseroff identified gets at the heart of Krysten’s work. Her poems engage with challenging personal, social, and politicized issues, with a particular focus on the difficulties black women face and have faced for generations. But she never lets you forget that understanding and appreciating our differences is the solution not the problem.

ECM: What are your visions and goals for the press? Where do you see publishing going in general?

RP: We’ve always strived to publish challenging books that people actually want to read. When asked, we’ve often said we seek writing that combines the cerebral with the visceral, which is just our fancy way of talking about something that makes you think and feel. We get a lot of submissions that lean one way or the other, but ultimately, we want both. That springs from conversations Carissa and I have had about contemporary literature and the patterns we see as readers and editors, and what we’d like to support in general.

On that note, our conception of reading and writing has grown, and over the last few years, we’ve found ourselves particularly engaged with writing as a catalyst for social action. Again, it’s a fancy turn of phrase, but that basically means we want to publish work that forges and fosters communities. At the very least, we want to reflect the reality of who we are as readers. Both Carissa and I are bisexual, and we’ve had a long commitment of supporting LGBTQ+ writers, and Carissa is multiracial, and she’s regularly trying to make sure writers of color know that we run a venue they can trust with their work.

As for publishing in general, I think that we’re seeing more people getting the opportunity both to publish and to be published. Structural changes in the publishing world over the last 10-15 years have done a lot to obliterate the monetary and technical barriers that existed. Those same changes have also allowed people whose voices were limited by traditional gatekeepers to have their voices amplified and to reach a larger audience.

One worrying trend I see, which extends beyond publishing to most facets of life, is the devaluing of the humanities. Many colleges and universities are shrinking or shuttering English/literature, foreign language, and philosophy departments (among others) because they don’t measure up financially. They’re also hiring fewer faculty into stable, full-time positions and reducing department funding for students’ professional development, all while raising tuition year after year. The bottom line has always been the wrong place to look if you want to understand the impact and power of education. When you diminish the subjects that aren’t profitable, you also diminish the value of an institution and the education it provides. There is no real substitute for gaining the ability to read deeply, think critically, and communicate effectively.

ECM: What’s in your reading pile, either from your press or from other presses?

RP: We’ve got a full-length manuscript to read by a poet who we’ve worked with from his very first publication, and we couldn’t be more excited to have the chance to see (and most likely work with him for) this project. Unrelated to work, I’m really excited about two small press books from two of my favorite poets: Randall Mann’s The Illusion of Intimacy from Diode Editions and Carl Phillips’ Star Map with Action Figures from Sibling Rivalry Press.

ECM: What advice would you offer someone looking to publish with you?

RP: This feels like the rote answer to give here, but read what we’ve published, and consider whether or not that work is in conversation with what you write. Our press is made up of people who are excited about working with writers. We want to edit and discuss and collaborate.

ECM: What advice would you offer someone thinking of starting a small press?

RP: Ask questions! I’ve rarely met people in the small press community who aren’t willing to talk about both their successes and their failures. You don’t need to repeat mistakes others have already made and the best way to do that is to learn from them. Get involved with a press as a reader or editor and see what it looks like from the inside.

Implied in that note: you’re going to make mistakes. Let yourself make them. Learn from them, forgive yourself, and do better next time.

Also—and this is a big one—don’t forget that any given book of poetry you’ve read and loved involved an incredible amount of work. If the publisher has done right by their authors, you’re mostly unaware of that work when you read a book. But, the work is there in that book, and in every book the press puts out. Running a press means reading submissions, editing (word-editing, line-editing, ordering, reordering, etc.), proofreading, designing, and printing. But, it also means running a business, filing taxes, calculating royalties, hosting events, finding a printer, mailing books, getting distribution, etc. Most of those parts are way less fun, but they’re no less important. Keeping it all in focus to reach the goals you’ve set for yourself is the hardest part and the most rewarding.

Learn more about Aforementioned Productions

Erica Charis-Molling is a creative writing instructor and librarian at the Boston Public Library. Her writing has been published in Crosswinds, Presence, Glass, Anchor, Vinyl, Entropy, and Mezzo Cammin. She’s an alum of the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and received her M.F.A. in Creative Writing from Antioch University.